News

Realignment means new money – and new headaches

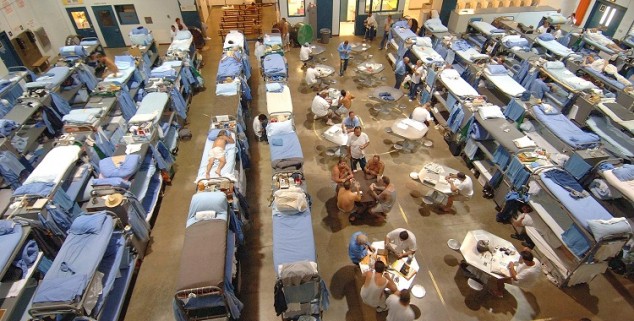

Overcrowding at California State Prison, Vacaville.

Overcrowding at California State Prison, Vacaville.The fast, unprecedented shift of state resources and responsibilities to California’s counties has meant money, headaches, new challenges, successes and uncertainty.

So after two years almost to the day, it’s time to take stock.

“It was done too quickly, without enough notice and not enough jail beds for local detainees,” said John Benoit, chairman of the Riverside County board of supervisors, referring to the transfer of state inmates to local custody.

The shift of some state prisoners to the county sheriffs is the most visible – and controversial — piece of realignment, Gov. Brown’s plan to transfer authority over numerous state programs to the local jurisdictions and supply them with the money to handle them. He sought the shift after federal judges ordered the state to reduce the number of inmates in its overcrowded prisons; the governor has appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

But the huge shift, some $6 billion a year worth of services, includes much more than inmate transfers.

“I think things are moving along okay on that front – we’re getting people into mental health treatment and we’re getting people into substance abuse treatment. On the whole, providing the services is still a work in progress for us,” Benoit said, whose large county with a mix of urban and rural areas is representative of the challenges of realignment faces by most counties.

Of the total realignment package, correctional and law enforcement services amount to just over a third of the funds. Social service and health-related programs account for the rest. In total, realignment entails about $5.5 billion from sales taxes and some $500 million from the Vehicle License Fee.

The funding stream has constitutional protections as well to make sure the money keeps flowing – protections that will continue after the temporary taxes approved last year in Proposition 30 expire.

That assurance, although not covered widely in the media, is crucial to realignment’s long-term success. “That certainly should not be underestimated,” said Elizabeth Howard Espinosa, a senior legislative representative at the California State Association of Counties.

But she also said that the funding sources reflect economic conditions and can rise or fall – which means the counties’ budgeting must reflect that volatility. “We benefit from the uptick and we have to plan for that,” she noted. “If we are properly resourced, we will have better outcomes at the local levels, when we get the money with the responsibility, we are happy to take it on.”

A county-by-county status report on the impact of realignment and the role of the locals appears to show that the hotly controversial program is stabilizing and taking hold in the prisoner shift and in corrections-related services. The survey of the counties provides a snapshot of local efforts.

“Through June 2013, the evolution of realignment has resulted in significant quantifiable measures at both the state and local level,” noted the report by the Board of State and Community Corrections.

The 135-page survey looked at the local community correctional panels that were set up in each county to oversee realignment. The panels, targeting law enforcement implications, are headed by the counties’ chief probation officers and include representatives of police, sheriff’s department, prosecutors, drug counseling services and others.

The locals’ vary in their respective pieces of putting realignment into effect, differing on their handling pre-trial, probation, intervention, reporting, release and myriad other issues. The state, the study said, “empowered each county to make local public safety decisions based on local needs,” while employing “the principles embedded in realignment of local decision making, based on local needs and local system capacity …”

System capacity is a critical issue. Since July 2011, the total average daily population, or ADP, of local adult detention facilities has increased. As of September 2012, the total ADP was 104 percent of the rated capacity and those charged with felonies in local custody was about about 4 percent.

‘Further, some counties operate jails under court-imposed population caps while other counties may have capacity to incarcerate more offenders,” the community corrections board noted in a separate report.

For the locals, potential for legal intervention in realignment is a wild card that could play out badly.

“We were one of the first counties to get sued by the state,” Benoit said. “Our jails were never built to be long-term housing facilities. It’s tough to meet those requirements. We’re spending $100 million to add 1,300 beds in Indio,” he added, noting the complexity and time frame – years– of getting jails built. “You know how long it takes to get a jail approved? You‘ve got six different state agencies and four different agreements, but they can’t agree among themselves so that we can meet the state’s deadline.”

At the end of the day, realignment clearly remains a work in progress.

“We’re still ramping up in many respects,” said Mark Hake, the chief probation officer of Riverside County. One of the biggest issues has been the shift of prisoners defined as “nons” – non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual offenders. “But that really is a misnomer that defines their current offense, rather than their entire criminal history,” Hake said.

“I think one of the biggest challenges we had in realignment was a very short period to implement this system and hire personnel and get them trained…We’ve had to hire a lot of staff having to supervise a population that is far more criminally sophisticated with very, very lengthy criminal histories,” he said.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply