News

A bare-knuckle brawl in the 7th Senate District

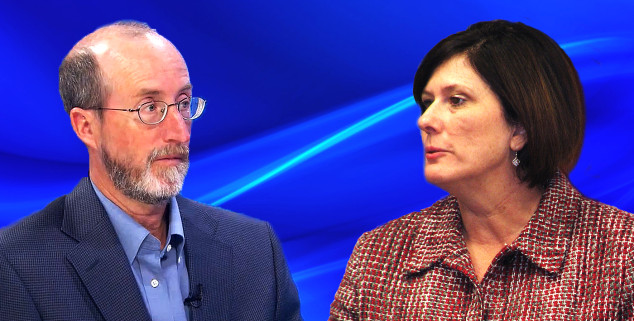

Candidates in the 7th Senate District: Orinda Mayor Steve Glazer and Assemblymember Susan Bonilla, D-Concord. (Photo illustration, separate images combined: Tim Foster, Capitol Weekly)

Candidates in the 7th Senate District: Orinda Mayor Steve Glazer and Assemblymember Susan Bonilla, D-Concord. (Photo illustration, separate images combined: Tim Foster, Capitol Weekly)Welcome to the 7th Senate District, where money and hardball politics came together in the primary election.

The runoff will not be much different.

Even in a state now accustomed to seven-digit spending in legislative campaigns, the 7th District showdown in May is likely to set records. And powerful interests that weighed in during the primary – organized labor, business interests, the dentists, the doctors and the fire fighters, for example – are all but certain to pony up again.

“They were all over the (primary) election, so why would they stay away now?” said one strategist.

Total spending in the March 17 primary hit $2.5 million, much of it by independent committees not affiliated with the candidates’ campaigns. In effect, the 7th Senate District — mostly Contra Costa County but a slice of Alameda County, as well — is the state in microcosm.

“A battle of the titans,” said veteran strategist Ray McNally.

The top two vote-getters on March 17 – Steve Glazer and Susan Bonilla – will confront each other May 19 in a runoff. Glazer, a political consultant, is the mayor of Orinda and served as Jerry Brown’s 2010 campaign manager. Bonilla, D-Concord, is an Assemblywoman and chair of the Business and Professions Committee, an influential Capitol perch with leverage over legislation sought – or opposed – by any number of special interests. Bonilla’s committee wields authority over a wide range of regulatory issues, including the creation of new entities in the Department of Consumer Affairs; the licensing of health care professionals, building standards and vocational education, among others.

Both are Democrats and both want to fill the seat vacated by Democrat Mark DeSaulnier, who left for Congress.

But there are distinct differences.

Glazer is business-friendly with links to the political arm of the state Chamber of Commerce, who opposed a strike by BART transit workers and who has supported public charter schools. He sees himself as “socially progressive and fiscally conservative,” a posture similar to that of Brown, and considers himself an outside reformer of a Capitol crippled by partisanship and special interests, a position that he believes reflects the views of many in the district.

Bonilla, the former mayor of Concord and member of the Contra Costa Counnty board of supervisors, was elected to the Assembly in 2010 following a four-year stint on the board. She points to her experience as a state and local elected official, and notes her role in reaching a landmark compromise on legislation she authored — closely watched nationally — that established rules for Uber and Lyft drivers to carry insurance. The governor signed the measure. If the pro-labor Bonilla doesn’t win in May, she will remain as head of the powerful B&P committee – a fact not lost on myriad interests.

“I have proven effectiveness and experience. To me, that’s the crux of the race,” Bonilla said. “I’m into policy, not politics.”

Los Angeles businessman Bill Bloomfield, increasingly a visible player in California politics, spent nearly $600,000 in independent expenditures on behalf of Glazer during a four-week period starting in early February.

The race has been a battleground for outside spending.

Political expenditure committees of the California Dental Association, the California Medical Association and the California Professional Firefighters spent at least $574,000 on Bonilla’s behalf, much of it in the final days before Election Night. The lion’s share, $336,000, came from the dentists, with the CPF at $155,000 and the CMA at $83,000.

Meanwhile, the California Chamber of Commerce’s political action arm, JobsPAC, spent $376,000 for Democrat Glazer.

And, in a twist, another independent expenditure committee, the Asian American Small Business Association PAC, which usually backs Democrats, weighed in with $68,000 to support Hertle – who wasn’t even running and had already backed Glazer. The group spent a similar amount to oppose Glazer.

Los Angeles businessman Bill Bloomfield, increasingly a visible player in California politics, spent nearly $600,000 in independent expenditures on behalf of Glazer during a four-week period starting in early February.

One major player, the California Association of Realtors, spent nearly $1.2 million on Glazer’s behalf last year in his unsuccessful, bruising bid for the 16th Assembly District, which ultimately went to Republican Catherine Baker. To the surprise of many, the group was not visible in the special election primary, but there’s speculation in the Capitol that CAR may get involved in the runoff. Whatever its plans, it’s not saying.

“You know how it is around here: people have long memories,” said one Democratic strategist.

The California Teachers Association, which spent some $700,000 against Glazer in the 16th AD race, is likely to play in the runoff, as is the California Labor Federation and an array of labor groups. During the past week, labor interests have raised more than $310,000, with more than half the donations coming from the State Council of Service Employees.

For Glazer, there’s a history here: He angered labor in 2012 when he worked for the Chamber of Commerce’s political operation, targeting liberal, labor-friendly Democrats in hopes of winning victories for more conservative Democrats. Two of them ultimately went down – Democratic Assemblymembers Betsy Butler of Marina Del Rey and Mike Allen of Santa Rosa. Later, Glazer came out in opposition to strikes by public transit workers, an issue that inflamed the public during the BART strike.

For many Democrats, he attacked the heart of the party’s base, and many Democrats have not forgiven or forgotten. “You know how it is around here: people have long memories,” said one Democratic strategist.

The California Labor Federation in 2013 placed him on a “do not hire” blacklist, contending that he had damaged the labor movement. Several other consultants were placed on the same list. As for JobsPac, it has in the past used a Democrat and a Republican to run its political operation, and it has endorsed some Democratic candidates.

“For us, the concern is the people who Glazer has aligned himself with,” said Steve Smith of the California Labor Federation, who said a coalition of labor groups would play a role opposing Glazer in the election, which means putting troops on the ground.

“The focus of our program is always the personal contact, hitting a lot of doors and doing a lot of mail,” Smith said.

Democrats have a 15-point registration edge, but there are concerns about low voter turnout, which traditionally dogs special elections. About a fourth of the district’s 486,000 registered voters actually cast ballots on March 17, according to the state elections officer.

And Republicans may have little reason to go to the polls on May 19 to vote for a Democrat, although Glazer hopes to tap into voters that supported Hertle.

“If you’re a Republican from this area, you are more likely to be socially progressive as opposed to socially conservative,” a moderate posture that reflects his own views, Glazer said. “There isn’t much of a Tea Party here; there are urban professionals.”

“The same goes for the Democrats,” he added. “The majority of the district are more likely to be white-collared Democrats, small business owners, much sensitive to financial matters. There is a large middle, a substantial center in this district. I’m a problem solver, not a partisan.”

But does appealing to Republicans as well as Democrats blur his own positions?

“He’s trying to be all things to all voters,” said Steven Maviglio, a Democratic consultant who is working an independent expenditure committee to defeat Glazer. “Democrats are not going to like that, and Republicans see clearly that he is not one of them, either.”

The California Democratic Party has officially endorsed Bonilla, as have three dozen legislators and an array of labor interests.

But the electoral math is daunting: Glazer captured a third of the vote in the March 17 primary, the high vote-getter among the five on the ballot, but going into the runoff he faces Bonilla, who got nearly 25 percent in the primary and who, presumably, will capture at least some of the supporters of Buchanan, who polled 22.5 percent. Another Democrat, Terry Kremin, got 2.8 percent. Glazer would have to get all of Hertle’s support – she polled 16 percent in the primary — and retain his all his base to approach a majority.

And then there’s the decline-to-state voters who comprise more than 22 percent of the district’s electorate. Which way will they break in the runoff?

“It’s going to be a very, very close race,” McNally said.

The California Democratic Party has officially endorsed Bonilla, as have three dozen legislators and an array of labor interests.

But in a district that is strongly Democratic, fissures and cracks appear among Democrats as they square off against each other, forcing intraparty tensions. Similar tensions arise statewide.

“That’s really symptomatic of a one-party state,” said Mike Madrid, a long-time Republican consultant and expert in Latino politics, and the publisher of newsletters targeting city and county governments.

“In Dem-on-Dem battles, the Republicans are becoming increasingly important,” he added.

“I lived through this with Republicans in 1990s,” he added. “I can tell you, this doesn’t end well.”

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

[…] Bonilla, the former mayor of Concord and member of the Contra Costa Counnty board of supervisors, was elected to the Assembly in 2010 following a four-year stint on the board. She points to her experience as a state and local elected official, and notes her role in reaching a landmark compromise on legislation she authored — closely watched nationally — that established rules for Uber and Lyft drivers to carry insurance. The governor signed the measure. If the pro-labor Bonilla doesn’t win in May, she will remain as head of the powerful B&P committee – a fact not lost on myriad interests. Read More > at Capitol Weekly […]