News

Sexual assault evidence in California: a slow moving story

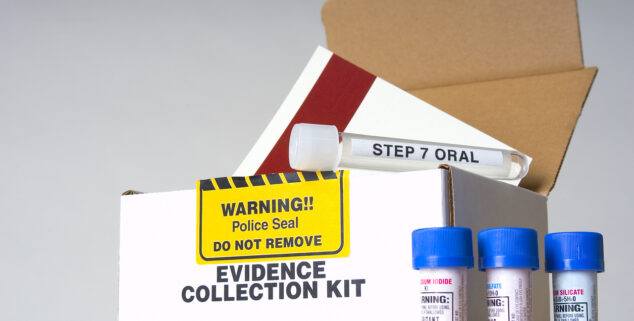

Image by BonnieJ via iStock

Image by BonnieJ via iStockAlmost a year after California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a measure (SB 215) allowing survivors of sexual assault to track and receive updates regarding the status of their sexual assault evidence kit, its authors are optimistic about the outcome.

Senator Anthony Portantino (D), a coauthor of the bill, says, “We’re getting good data to show that it’s working.”

As that data continues to be processed, question remain on how a rape kit is dealt with and why there is such a backlog in processing them.

Ilse Knecht, Director of Policy and Advocacy at the Joyful Heart Foundation, an advocacy group for sexual assault survivors, has spent two decades working on this issue. In 2001, as Director of Public Policy at the National Center for Victims of Crime, she worked on the Debbie Smith Act (Rep. Green, R-WI-8), which ultimately passed through Congress and was signed into federal law in 2004. That law requires states to create plans to reduce their backlog of rape kits, as well as providing funding for crime labs to process DNA evidence.

She remembers being shocked to learn the scope of the national rape kit backlog.

“At that time there were kits that were sitting for years and years and years, and never being tested,” she says.

After being brought into the Joyful Heart Foundation with the goal of creating a legislative campaign to end the backlog, she helped launch a legislative initiative with the six pillars of reform in 2016.

The goal is for each state to meet the standards of all six pillars of reform. California currently meets five out of the six, falling short on the pillar of testing backlogged kits.

Knecht says California has only recently begun to take a legislative approach to dealing with its backlog of rape kits, the first coming in 2015 by then-Assemblymember Nancy Skinner. That measure, AB 1517, created a timeline on which rape kits in California must be tested and submitted to the national database of DNA profiles.

That was followed in 2019 by Senate Bill 22, authored by Senator Connie Leyva (D), which requires law enforcement agencies to “submit sexual assault forensic evidence to a crime lab or ensure that a rapid turnaround DNA program is in place, as specified, and require a crime lab to either process the evidence or transmit the evidence to another crime lab for processing.”

Knecht stresses the importance of this process being mandated by law, saying that before its passage, “The decision to test a kit was coming down to one person” who might have any number of biases.

And where does California stand now compared to the rest of the country? Still not great, Knecht says.

“It’s been a little slow-moving,” she says. “Every year we chop off something else. We have other states that did reform very quickly. I think now it’s 18 states that have ended their backlog. We’ve done a lot of other things. We’ve got mandatory testing…victim’s rights to know the status of their kit, we’ve got this tracking system…the last issue is this backlog.”

Another concern, specifically in California, is that the backlog itself is not fully accounted for, she says.

California has only recently begun to take a legislative approach to dealing with its backlog of rape kits.

“Frankly we don’t know how many are on the shelves, because the inventory is incomplete. There were 149 police agencies and crime labs that participated in the audit, but there are about 700 agencies in the state, so that’s very telling. The law also required medical facilities to provide information and none of them did… It’s a partial number and even then it came out to almost 14,000.”

In order to properly address the backlog, she says, there needs to be a proper analysis of the accurate number of kits in need of testing.

“We’d like to see another inventory.”

To help with that, Assemblymember Tom Lackey, a Palmdale Republican, is authoring a bill (AB 1368) this session to require law enforcement agencies to submit any tests or DNA evidence they may have received by January 2025.

Despite support from Knecht’s organization, Assemblymember Lackey says he has tried to put the bill through before, and been shot down. Senator Portantino says he had a similar experience while in the Assembly with a bill (AB 322) he introduced there in 2018.

“When originally it was brought forth, people focused strictly on the fiscal aspect, and not on the human aspect,” he says.

Money is always a concern, especially now with the state facing a significant budget deficit. However, Lackey says that this is not a strong argument.

“The state has at least $6 million sitting in an account at the DOJ to bring about what we’re asking for. I championed a request for $4 million, and Assemblymember Evan Low, a Bay Area Democrat, has a voluntary tax fund for $2 million, and both of those funds are still just sitting there, so it’s a weak argument,” Lackey says.

There are also issues around control, he says.

“They claim we’re trying to micromanage the lab. All we’re asking is that you do what you’re hired to do.”

Portantino and Knecht say they struggle to understand why it has taken so long to begin with.

“It’s a commentary on society that it had to become a crisis before it was addressed,” Portantino says.

“This is a public safety issue,” Knecht says. “It should be prioritized.”

Claire McCarville is a Capitol Weekly intern. She is a junior at Arizona State University.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply