News

Rosalynn Carter: A lifetime voice for improving mental health care

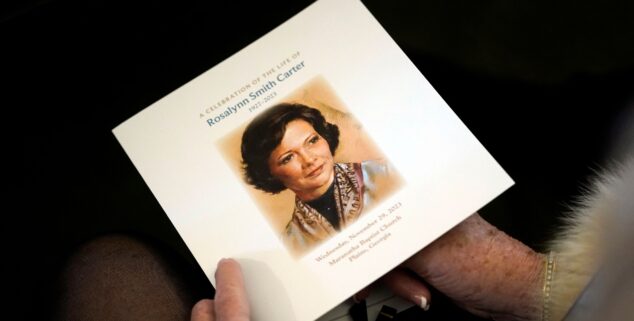

First Lady Rosalynn Carter, photo courtesy of AP

First Lady Rosalynn Carter, photo courtesy of APTributes to First Lady Rosalynn Carter invariably cite her lifelong commitment to improving care for people with severe mental illness. As she stumped for her husband during the closing days of the 1976 presidential campaign, she brought that advocacy to the unlikely locale of Bakersfield.

Like many others drawn to the issue, Mrs. Carter, who died on Nov. 19, had a personal story. As a young girl, she would hide when she saw a particular cousin walking down a street and singing loudly.

“I don’t know why I had to get away – he was never violent, just very nervous and very loud,” she wrote in her 1984 memoir, “First Lady from Plains.”

Later, during Jimmy Carter’s winning run for Georgia governor in 1970, she told of being struck by the number of people she met on the trail who struggled with mental illness or who had family members who were mentally disabled.

“The issue of mental illness began to prey on my mind,” she wrote.

At her encouragement, Gov. Carter elevated the issue, shrinking the Georgia state hospital population by greater numbers than any state other than New York. Unlike many states in the 1970s, California among them, Gov. Carter used state funds to expand the use of community mental health care centers.

As a young girl, she would hide when she saw a particular cousin walking down a street and singing loudly.

As Georgia’s First Lady, Mrs. Carter volunteered at one of those centers, and presided over Georgia’s Special Olympics. She carried that passion to the heart of California’s oil patch on Oct. 15, 1976, three weeks before election day, as Carter sought to place California, then a Republican-leaning state, in play.

On that day, Mrs. Carter attended events with candidates for state offices and headlined a fundraiser for Kern County Democrats. As she did whenever she traveled, Mrs. Carter took time to find a phone to call home to her daughter, Amy, who was 8. And she took an afternoon tour of the Kern View Mental Health Center and Hospital in Bakersfield.

Founded by Mennonites and funded by federal money from legislation signed by President John F. Kennedy in 1963, Kern View was the main mental health care provider in a county that at the time had a population of 400,000. It offered preventive mental health care, outpatient services for people with ongoing issues, and had 26 beds for individuals in crisis.

Afterward, appearing before a gathering of about 100 people, she promised that if her husband were elected, she would urge him to establish a commission to assess the nation’s mental health needs and determine how Uncle Sam could help.

“We are spending $20 billion a year on the care of the mentally disabled. Less than one-half of one percent of this total is for research into the causes,” she said, as reported by the Bakersfield Californian.

Carter lost California narrowly, but Mrs. Carter’s promise became reality when, on Feb. 17, 1977, President Carter issued an executive order creating the President’s Commission on Mental Health, and made Rosalynn Carter its honorary chairwoman.

The First Lady convened hearings of the commission in Philadelphia, Chicago, Tucson and San Francisco. Mayor George Moscone was at San Francisco International Airport to greet her on June 21, 1977, as she stepped off the jet, bundled in an overcoat and scarf, prepared for the windy 50-degree summer day.

Amy was by her side, holding a yellow stuffed lion on her first trip to what boosters called The City that Knows How. The first daughter got the grand tour the following day–Exploratorium, Golden Gate Bridge, the aquarium at Golden Gate Park, and a cable car ride–while her mom presided over a day-long hearing at the Sheraton Palace Hotel.

Moscone, the first speaker, was a state senator in 1967 and voted for the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, the landmark law that sped the emptying of state hospitals and provided greater civil rights protections to people with mental illness. As mayor, he contended with rising homelessness.

“We must make our highest priority the needs of the most severely afflicted,” Moscone told the commissioners, making clear that the crisis of untreated mental illness was worsening.

When Gov. Jerry Brown’s Health & Welfare secretary, Mario Obledo, took his turn to speak, one of the commissioners told Obledo that she was “very impressed with the numbers of people being deinstitutionalized” in California, then asked: “But do you feel like they’ve been accommodated back in the community?”

Obledo answered: “No. No, they have not, and that’s one of our biggest problems. …

“The people have been moved out of the state hospitals into communities and I don’t believe that government – whether it’s been federal, state, or local – have met their commitment to the people that have been placed into the community.”

Republican Assemblyman Frank Lanterman, the architect of the law that bore his name, left a budget hearing in Sacramento early and sped 90 miles to San Francisco to testify.

Mrs. Carter had cautioned that her husband did not appreciate wordy memos and was tight with money. Clearly, that advice was not heeded.

Running over his allotted time, Lanterman, in his final term in office, recounted his history on the issue dating to the 1950s and urged the commission to provide more money to counties.

“The dollar has not followed the patient,” he told the First Lady. “In the rip-off of the dollars for the state hospitals, the dollar has not followed the patient.”

Once the roadshows concluded, commissioners got down to the task of summing up what they learned. Mrs. Carter had cautioned that her husband did not appreciate wordy memos and was tight with money. Clearly, that advice was not heeded.

In April 1978, the commissioners delivered a 2,140-page report in four volumes with 117 recommendations, 42 of which were made by one subpanel. President Carter offered diplomatic words for the commission’s effort, writing in his book, “White House Diary”:

“Rosalynn and her twenty members really worked hard and did a good job. They got an enormous amount of publicity on radio and television, also the news, and I’ll do my best with their recommendations.”

The president returned to the issue on May 15, 1979, writing in his diary that he, Mrs. Carter and Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Joseph Califano unveiled the Mental Health Systems Act, an ambitious proposal to expand the federal government’s role in mental health care.

In the Senate, the task of shaping the Mental Health Systems Act fell to Sen. Edward M. Kennedy. That was awkward. The Massachusets Democrat was challenging Carter for the Democratic Party nomination in 1980.

Rosalynn Carter placed politics aside, becoming the first First Lady to testify to Congress since Eleanor Roosevelt spoke on behalf of coal miners.

“I had to swallow some pride – for the cause – during the campaign of 1980 when Senator Kennedy one day would be on the stump making one of his statements such as ‘President Carter is making the poor eat cat food,’ and the next day would be saying to me, ‘Mrs. Carter, the committee is completing work on the Mental Health Systems Act,’” she wrote in her memoir. “We continued these courtesy calls even during the worst part of the campaign.”

Congressman Henry Waxman, a Democrat from West Los Angeles who had endorsed Kennedy’s presidential bid, crafted the House version. Having served six years in the California legislature, he was well acquainted with the issue, and had been among the liberals who pushed Gov. Ronald Reagan to provide more funding for community mental health care.

The Mental Health Services Act was a tough sell.

From the left, Barbara Mikulski, the Maryland Democrat then in her first year in Congress, said at the bill’s first hearing that she was torn over whether to try to improve the bill or to attempt to kill it outright, saying the early version of the measure seemed to be “a mushy rationalization for what I consider the dumping of people from institutions.”

William Dannemeyer, a hard-right Republican from Orange County California and someone Waxman considered a “truly awful human being,” was equally blunt, if bizarre.

Congress then was very different from the Congress of today. It functioned in 1980, and the Mental Health Systems Act, a tome of more than 50,000 words, passed by comfortable margins in both houses.

“I would suggest for your consideration that one of the factors that is causing the mental illness, or the mental instability, or the emotional instability, of American people is the high level of taxation which they are sustaining,” Dannemeyer said at the opening hearing in July 1979.

Congress then was very different from the Congress of today. It functioned in 1980, and the Mental Health Systems Act, a tome of more than 50,000 words, passed by comfortable margins in both houses. Dannemeyer surprised no one by voting against it, though more significantly, so did a young Republican congressman from Michigan, David Stockman.

On Oct. 7, 1980, President Carter and the First Lady flew by helicopter to Annandale, Virginia, to, as he wrote in his diary, “meet with Senator Kennedy and others,” and sign the Mental Health Systems Act into law. The backdrop was one of the community mental health centers funded by JFK’s 1963 legislation.

Congressman Waxman, who had done most of the work on the bill, learned of the bill signing event late. Perhaps it was an oversight, though Waxman turned it to his advantage. His teenage daughter happened to have been with him on that day, and he was able to arrange a Marine helicopter flight to the event, a move, he recalled with some amusement in a recent interview with me, that impressed the teenager.

In his remarks, Carter called Kennedy his “good friend.” Kennedy focused his remarks on the First Lady. The legislation, he said, was a “living monument to her commitment” to people with mental illness.

He harkened back to his brother and called the Mental Health Systems Act the “most significant step forward in this area since 1963,” when President Kennedy lamented that people who had developmental disabilities and mental illness had been neglected for too long.”

“This legislation represents new and important progress towards making such care a right for all those who need it,” Kennedy said.

Carter, battling to keep his job, used the event at least in part to demonstrate Democratic unity a month before election day. To that extent, it was a success.

On the following day, the New York Times headline read: “Carter, Joined by His Wife and Kennedy, Signs Law Reorganizing Mental Health Services.” An accompanying photo showed the President, Mrs. Carter and Kennedy.

A month later, Ronald Reagan defeated him in a landslide, and selected David Stockman as his chief budget officer. Shortly after taking office, In March 1981, Stockman let the press know that he would be recommending major cuts in social welfare spending, including mental health care.

Reagan signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 in August. On pages 560 and 561 of the 903-page bill, in the turgid language of Congress, two paragraphs gutted the law that took four years to produce.

Reagan signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 in August. On pages 560 and 561 of the 903-page bill, in the turgid language of Congress, two paragraphs gutted the law that took four years to produce.

Rosalynn Carter returned to Washington that October. Reporters, focusing on the shiny object of the day, led with Mrs. Carter’s oblique criticism of First Lady Nancy Reagan’s purchase of new China for the White House. But in the body of some of the stories, reporters quoted Mrs. Carter’s view of Reagan’s stripping money from the Mental Health Services Act:

“It’s going to cost the country untold sums, not only of money but also in human lives.”

During his four years in office, Carter left many lasting imprints. He encouraged solar energy, expanded immunization, took strides toward peace in the Middle East, stood against Russia’ invasion of Afghanistan, and lifted Prohibition-era restrictions that spawned the craft brewing industry. At the urging of Mrs. Carter, his partner of 77 years, President Carter also sought to improve the lot of people with brain disease. If that measure had not been gutted, perhaps the crisis on the streets today would not be quite so severe.

On her trip to Bakersfield in the 1976 campaign, Rosalynn Carter offered hope for a greater federal role in mental health care. It wasn’t to be. Federal money for the clinic she visited dried up years ago. At last count, 1,948 Kern County residents were unhoused, 530 of whom reported a serious mental illness.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply