News

Public banking movement gaining traction in California

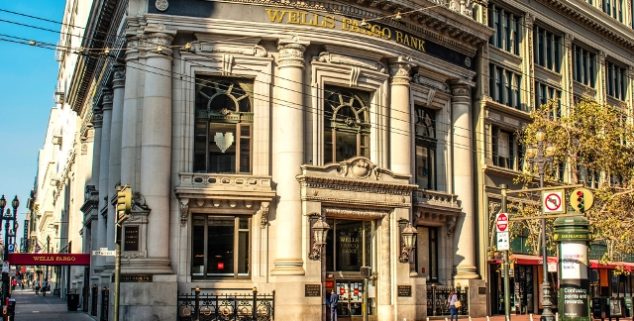

Historical building of Wells Fargo in San Francisco's financial district. Photo: Takako Hatayama-Phillips, via Shutterstock)

Historical building of Wells Fargo in San Francisco's financial district. Photo: Takako Hatayama-Phillips, via Shutterstock)San Francisco has taken its first major step toward establishing a public bank, and other California municipalities are also moving forward in exploring public banking, including a regional effort by cities and counties on the Central Coast.

The moves come nearly two years after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 857, enabling California cities and counties to form public banks. These are locally-controlled financial institutions into which municipal revenues — such as taxes and fees — are deposited. The money is then lent out to small businesses and infrastructure projects, among others, through partnerships with community banks. The goal is to directly benefit residents, while providing not-for-profit services for citizens who choose to use the bank.

“We finally have the option of reinvesting our public tax dollars in our local communities instead of rewarding Wall Street’s bad behavior.” — David Chiu

A state public bank was formed in North Dakota more than a century ago, although no cities or counties in the nation have public banks. But the California statute reportedly is adding fuel to a nationwide public banking effort.

By law, a public bank in California must be run by banking professionals responsible to a board and overseen by California’s Department of Business Oversight.

“We finally have the option of reinvesting our public tax dollars in our local communities instead of rewarding Wall Street’s bad behavior,” Assemblyman David Chiu, a San Francisco Democrat and coauthor of AB 857, said at the time of the governor’s signing.

On June 15, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors unanimously approved the San Francisco Reinvestment Working Group ordinance. Penned by Supervisor Dean Preston, the ordinance authorizes the creation of a working group made up of financial experts, community members, and representatives of the city’s Controller and Treasurer.

The working group has one year from its first meeting to create a business plan to present to the Board of Supervisors and Local Agency Formation Commission, which, if approved, will be submitted to the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation.

Cities and counties on California’s Central Coast are in the starting stages of creating a regional public bank.

However, before the working group can convene, it must be funded. Currently, there is no money earmarked in the mayor’s proposed budget to support a reinvestment working group.

The creation of the working group is the latest in San Francisco’s decade-long drive to establish a public bank which includes dozens of hearings, meetings and studies, including last year’s Municipal Bank Feasibility Task Force Report. That study outlined three possible routes that San Francisco get into public banking, all of which, if approved, will take years to see to fruition.

Cities and counties on California’s Central Coast are in the starting stages of creating a regional public bank.

Led by Santa Cruz County, resolutions supporting a Central Coast Public Bank viability study have been passed in Monterey and Santa Barbara counties, as well as the cities of Santa Cruz, Capitola, Seaside, Scotts Valley, Del Rey Oaks, and Watsonville.

In a unanimous vote, the city’s Economic Development and Jobs Committee approved the motion for the formation of the Municipal Bank of Los Angeles.

According to Santa Cruz County Supervisor Zach Friend, San Benito and San Luis Obispo counties have also been asked to back a viability study. Currently, neither county has signed on. The viability study is the first step municipalities must take to create a public bank.

In May, Los Angeles made progress in its quest for a public bank. In a unanimous vote, the city’s Economic Development and Jobs Committee approved the motion for the formation of the Municipal Bank of Los Angeles. The motion now goes before the full city council, though no date has been set for its hearing.

North Dakota, through the efforts of its farm community, established a public bank in 1919, an institution that has survived Great Depression, widespread bank and savings-and-loan failures, and the Great Recession. If San Francisco, Los Angeles, or the Central Coast are able to establish their own, it will be the first for an American city or county.

Public banks have the potential to “save local governments money, increase investment in affordable housing, infrastructure and other essential items.” — Zach Friend

While public bank proponents point to the Bank of North Dakota (BND) as a success story, critics of public banking counter that both BND’s scale and when it was established render such comparisons moot. Other critics, such as the CATO Institute’s Mark Calabria, use public bank failures from the 1800s in states like Vermont and Indiana as proof that public banking is a disaster waiting to happen.

The public banking law “infers that banks are not serving their communities, an argument repeatedly made by public bank activists in a variety of forums,” wrote the California Bankers Association, a leading public banking opponent. “Commercial banks, particularly community banks, will be harmed by the taking of local agency deposits which would otherwise be used as a source of liquidity by these banks to make loans into their communities.”

But supporters of public banking aren’t buying it, saying the public banks would retain revenues for the community and save the costs associated with private banking, among other benefits.

Public banks have the potential to “save local governments money, increase investment in affordable housing, infrastructure and other essential items,” says Santa Cruz’s Zach Friend.

“At a minimum, it’s important to explore the viability and possibilities of the formation and then to see whether this model makes sense for our region,” he added, “any method that would help improve investments in these challenges and save money to our communities is worthy of serious exploration.”

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply