There’s been some suggestion from Sen. Robert Hertzberg and others that expanding the sales tax would stabilize our tax base. That approach was rejected when it was recommended by the Parsky Commission in 2009, but Hertzberg wants to have the conversation again.

Another possibility is moving toward a system that is more property-tax based.

Property taxes don’t technically go to the general fund, but in reality, they determine billions of dollars in state spending. Think of it as a $50 billion shell game. The locals raise and spend property taxes, with billions going to schools. But they are reimbursed for that school spending by Sacramento.

As the LAO’s property tax whiz Chas Alamo explains, increased property taxes, therefore, can decrease the state’s education spending.

Some data provided by the Alamo and the LAO offers some compelling evidence that a budget driven by property tax revenues would be much more stable than the income-tax based system we’ve created over the last four decades.

When Proposition 13 passed in 1978, income taxes comprised 28.2 percent of the general fund revenues. Today, they’re equal to about 66 percent.

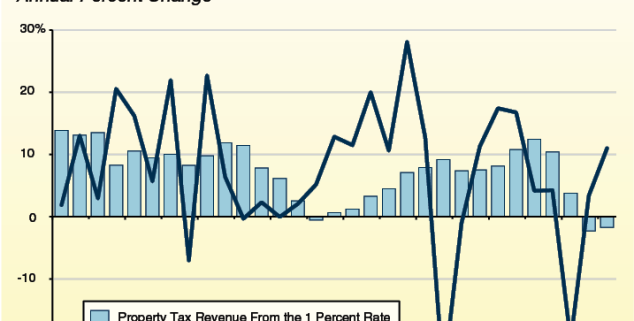

Since 1978, the state’s property tax revenues have fallen below the previous year’s totals only twice – with 1% drops each in 2009-10 and 2010-11, as the state coped with the housing crash.In all, there’s been an average of 5% annual growth in property tax revenues over the last 20 years, with the largest single year increases coming in 2005-2007, during the state’s housing boom. (To learn all you ever wanted to know about the state’s property tax, check this primer from the LAO)By contrast, income taxes have varied wildly. We’ve seen annual double-digit percentage increases in income tax revenue growth in 11 of the last 20 years. We’ve also had two massive drops in annual revenue of 26 %and 20% in 2001-02 and 2008-09 respectively.

In short, property taxes are far more stable than income taxes. They provide predictable growth, and seem to be virtually recession-proof.

Income taxes, by comparison, are subject to the whims of Wall St., taking the state’s finances on a roller coaster ride as they rise and fall. This is exacerbated by the fact that the state has grown more dependent on income taxes over the last 40 year.

When Proposition 13 passed in 1978, income taxes comprised 28.2 percent of the general fund revenues. Today, they’re equal to about 66 percent.

Could some sort of income for property tax swap be part of the answer? It’s an idea worth talking about.

By the 2013-14 budget year, personal income taxes accounted for two-thirds of all general fund revenues.

By comparison, property taxes that same year were equal to about 51% of the general fund. Moving to a property-tax based system may also be a way to ensure sustainable, but more controlled budget growth.

Of course, considering such a system means changing Proposition 13 and Proposition 98, a virtual political hornet’s nest. But part of the idea of this project is to get past the knee-jerk emotional political reactions in hopes of having an honest discussion about whether these ideas are good for the state. If there is strong leadership and a sustained effort to educate, voters can be convinced to go along. The campaign for Proposition 30 proved that.

The next step in the state’s long-term fiscal stability may be breaking our dependence on income taxes. But how? Could some sort of income for property tax swap be part of the answer? It’s an idea worth talking about.

Monkeying with the tax system is complicated business. It would inevitably create winners and losers, and would require approval from voters. But if done correctly, it could bring predictability and stability to our state’s revenue system.

—

Ed’s Note: Anthony York, a former editor of Capitol Weekly and former reporter for the Los Angeles Times, is the editor and publisher of The Grizzly Bear Project, which examines critical California policy issues, including wealth disparity.

Leave a Reply