News

By several measures, the FPPC is outnumbered

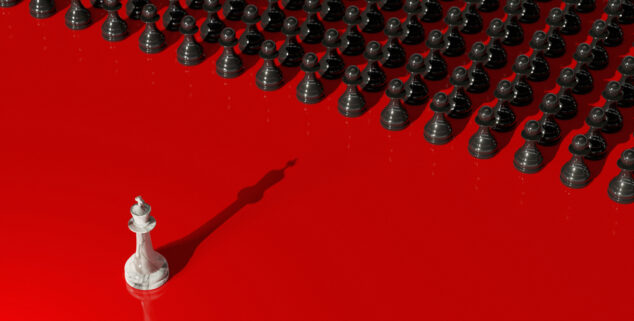

Outnumbered, image by Hernan E. Schmidt

Outnumbered, image by Hernan E. SchmidtIt’s easy to see that the Nevada Gaming Control Board is overmatched.

The agency, in charge of regulating gambling in the Silver State, employs around 400 people – and oversees more than 100,000 slot machines at 330 locations, to say nothing of the untold hundreds upon hundreds of table games and licensed gaming workers its staff also must monitor.

Clearly, the amount of gambling the control board must supervise far outstrips its staffing.

But how do you assess the scale of the job facing the California Fair Political Practices Commission? That’s less obvious.

The agency employs more than 90 people – attorneys, investigators, auditors, political reform consultants and support staffers – “to promote the integrity of state and local government in California through fair, impartial interpretation and enforcement of political campaign, lobbying and conflict of interest laws.”

That’s a broad mandate. How do you even begin to measure the scope of its mission?

Well, the California Legislature has 120 members. Each member likely had to defeat at least one other candidate for their office, so that’s roughly 240 legislative candidates to regulate. There are eight statewide constitutional officers – again, each likely facing at least one opponent in an election. That’s another 16 candidates to oversee.

More than 3,000 special interests are registered as lobbyist employers in the state. More than 1,500 bills are introduced in the legislature each session. So that’s a lot of legislative activity and lobbying for the FPPC to track.

During those unremarkable four weeks, the number of political filings was roughly 12 times greater than the total number of people working for the agency charged with overseeing the accuracy and legality of those very filings…And that was a slow month.

There are 482 cities and 58 counties in California, each with their own governing bodies, full of politicians who had to win elections for their jobs and who have their own slate of policy proposals and lobbying activity the FPPC has to supervise as well.

That’s one way to begin to estimate the size of the regulatory burden the FPPC’s more than 90 staffers carry, and it’s certainly nothing to sneeze at. But there’s another way to look at it too: the number of Political Reform Act disclosures the agency is responsible for ensuring their accuracy and transparency.

The California Secretary of State posts scores of documents on Cal-Access, reports and other disclosures that serve as the backbone of the regulatory oversight the FPPC provides. During campaign season or at the end of each quarter, the Capitol community is quite aware that Cal-Access becomes inundated with new disclosures. That’s no surprise.

But what about during slow periods, those seemingly rare times when there aren’t any big campaigns, or fiscal quarters ending? How much filing activity happens then?

Luckily, we have just concluded such a period. The four weeks from June 1 to June 28 have to qualify as some of the slowest in the current California political cycle. It’s not an election year. There were no special elections during that time. It also, critically, didn’t include the end of a quarter, when lobbying firms and lobbyist employers have to file reports with the SoS.

So to assess what happens during such a slow time, Capitol Weekly counted all the daily filings for lobbying activity and campaign finance made during that four-week period.

There were more than 1,200.

In other words, during those unremarkable four weeks, the number of political filings was roughly 12 times greater than the total number of people working for the agency charged with overseeing the accuracy and legality of those very filings.

And that was a slow month.

And those employees include support staff, like IT workers and secretaries, people who don’t directly work to enforce the Political Reform Act. (In fact, the FPPC’s Enforcement Division has more than 30 people in it.)

In other words, California’s political regulators – the people tasked with ensuring the integrity of the Golden State’s political process – are woefully outnumbered in even the easiest of times.

The FPPC doesn’t have the capacity to review all the daily filings when it’s slow during the political cycle. So, it doesn’t even try.

The FPPC finds violations of the Political Reform Act in a few different ways, through complaints filed with the agency by members of the public (who, in truth, are usually the political opponents of the subject of the complaint), through referrals from other agencies, through proactive cases agency staff see in the media and through a limited number of audits of disclosures by FPPC staff. In fact, it was through one of these audits that the FPPC broke the Kinde Durkee embezzlement scandal more than a decade ago.

Ann Ravel, who aggressively led the FPPC when the Durkee scandal broke in 2011 and later served on the Federal Election Commission, said that in a “perfect world” the agency would have the resources and staff to proactively review many more disclosures filed with the state.

The FPPC doesn’t have the capacity to review all the daily filings when it’s slow during the political cycle. So, it doesn’t even try.

“It should be a priority,” she said of political regulation. Given California’s size and power and highly politized culture, Ravel said the Golden State could, at least in theory, be a prime candidate for all kind of serious political shenanigans, including interference of foreign governments in elections.

But adding to the FPPC’s budget, or even developing ways to make its processes more efficient, aren’t major topics of discussion in Sacramento. It’s frustrating, Ravel said, especially since “We know there’s a ton of money in elections in California.”

Indeed, the Associated Press recently reported that many secretaries of state across the country are worried about misinformation in the 2024 elections.

FPPC Chair Richard Miadich acknowledged in an interview with Capitol Weekly that “the state budget is what it is” and noted that any enforcement agency probably wants more money and staff.

“Our staff is probably never going to keep pace with the number of complaints” it receives, he said.

But Miadich said some lawmakers are keenly interested in the FPPC’s mission and that the commission itself is doing everything it can to work within its fiscal constraints to ensure the integrity of the political process.

That’s meant focusing on adding new positions – specifically to the Enforcement staff – when possible, while also streamlining the process to focus the most resources on the most egregious violations.

Miadich said the Political Reform Act is complicated and filers are going to make mistakes – especially if they’re first-time candidates. As a result, he said, the FPPC has created programs and initiatives to move those minor mistakes through the system quickly, so that more attention can be given to serious cases involving money laundering or politicians using campaign funds to enrich themselves.

One of those programs is a sort of “traffic school,” where first-time candidates who file a disclosure incorrectly are given the chance to take an education course in lieu of paying a fine. That can help alleviate the regulatory burden on FPPC staff, opening up the door for more proactive enforcement efforts.

But Miadich also acknowledged proactive enforcement is a “resource-heavy endeavor” and the state budget is tight right now, even if political integrity is a hot topic nationwide.

“I feel we’re getting as much support as we can,” Miadich said, “given fiscal realities.”

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply