News

Dan Richard, bullet train conductor

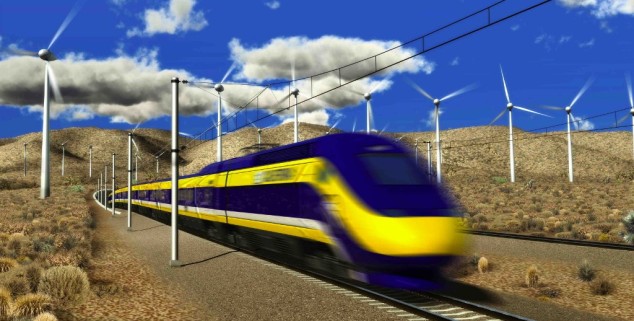

An artist's rendering of the California bullet train. (Photo: HSR)

An artist's rendering of the California bullet train. (Photo: HSR)Dan Richard, the chair of the California High Speed Rail Authority, is a man in the middle. The middle of court fights, the middle of political fights, the middle of a fight over California’s future.

“The rest of the developed world has moved energetically to adopt high-speed rail. We will too,” Richard says.

He may be right.

After miscues, battles over the bullet train’s routes and funding, and fierce opposition in California and Washington, there seems to be light at the end of the tunnel.

The crux of the opposition to the bullet train comes from Republicans, led by the House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield. Their discontent focuses on the cost.

Late last month, an appeals court overturned a lower-court decision and ruled that the state had met the requirements to develop its funding plan for the $68 billion project, a price tag that had been dramatically scaled back from about $100 billion.

Meanwhile, Gov. Brown, who is pushing hard for the bullet train, signed a state budget that provides hundreds of millions of dollars in cap-and-trade auction funds for the project – a move that immediately drew interest from an array of private investors. And preliminary work is starting on a 130-mile stretch in the Central Valley and planning is being expedited on a 40-mile segment in L.A. County.

The appellate court noted that additional legal obstacles loom, but for now, at least, the project appears on track.

Richard is no stranger to transportation battles – he spent more than two decades on the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) board of directors. But this time, the public works and business veteran may be in the most important fight of his career.

The crux of the opposition to the bullet train comes from Republicans, led by the House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield. Their discontent focuses on the cost.

Dan Richard, chairman of the board, High Speed RaIL Authority. (Photo: HSRA)

That $68 billion is a heady number in a state struggling with the needs of education, health, water, housing, unfunded public pension debt and deteriorating infrastructure, just to name a few problems. The cost more than four times the most expensive single public works project in the nation’s history, the $14.6 billion “big dig” in Boston, and 10 times the cost of the Bay Bridge overhaul.

In a conversation with Capitol Weekly, Richard discussed the cost issue.

“Many of the criticisms about the cost of high-speed rail stem from a lack of understanding of what’s involved in the numbers,” he said.

“They include the costs of an infrastructure of connecting rail lines and transportation hubs that will provide the state with the kind of total transportation system needed for our future growth as California’s population grows to an estimated 60 million by 2050. So they’re vastly more than the cost of high-speed rail itself,” he added.

It became clear to some that California’s growing population was putting an ever-increasing burden on its highways, airports and conventional passenger rail lines.

But what about the people who will be uprooted from their homes and farms as a result of the effort? Despite the provisions for restitution, that can be a bitter pill for them to swallow — and a memory not likely to fade in the near future.

Brown has been unequivocal in his support of high-speed rail, making it a keystone of his administration’s plan for the future of a state with the world’s eighth-largest economy and a gross state product of more than$2 trillion.

But opposition is intense. McCarthy has been active in an attempt to leverage federal resistance to the project, calling the project’s business plan “deeply flawed”. And the Republican-controlled House has voted against the projects continuation for four straight years. If the U.S. Senate swings next year to a Republican majority – the opposition in Washington could intensify.

Some Democrats also have been critical.

Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, a likely contender for governor after Brown leaves office, added his voice to the chorus of dissenters. Sen. Kevin De Leon, who is taking over the Senate leadership from termed-out Senate President Pro Tem Darrell Steinberg, labeled the project’s plan to start in the Central Valley a “train to nowhere” (for which he later apologized), and Sen. Mark DeSaulnier, D-Concord, a congressional candidate who chairs the Senate’s Transportation Committee, has said he is “not comfortable” with the plan for high-speed rail. Other criticisms have come from both sides of the aisle.

Controversy has followed high-speed rail from the moment it was first pushed in the early ‘80s, as it became clear to some that California’s growing population was putting an ever-increasing burden on its highways, airports and conventional passenger rail lines. But some argued that Californians’ love for automobiles meant that a bullet train would be vastly under-utilized.

But the federal government identified it as one of five national corridors for high speed rail planning and the California High-Speed Rail Commission was created by the State Legislature. A business plan was subsequently issued and the Senate authorized a $9.95 billion bond measure to finance the system. The bond measure was ultimately taken to the voters and approved by them in 2008 and Governor Jerry Brown identified it as a priority for his administration.

As board president at the Bay Area Rapid Transit District, he led efforts to secure $4 billion in capital for the transit system’s expansion to the San /Francisco Airport along with seismic retrofit and other rehab programs.

The Senate Budget Act of 2012 approved almost $8 billion in federal and state funds for the initial construction of the line in the Central Valley and 15 bookend and connectivity projects throughout the state. The plan also calls for billions of investment dollars in rail modernization that will improve local and regional lines and fulfill Richard’s claim of its meeting 21st century transportation needs.

Those are the infrastructure efforts that Richard says are often misunderstood.

Richard contends that high-speed rail will connect the state’s regions and contribute to economic development in a host of ways, including creation of much-needed jobs and a cleaner environment, while preserving agricultural and protected land.

The plan calls for the system to run from San Francisco to Los Angeles in under three hours at speeds capable of 200 miles an hour by 2029. It will eventually extend to Sacramento and San Diego and 24 additional stations.

Richard is no stranger to difficult undertakings. As board president at the Bay Area Rapid Transit District, he led efforts to secure $4 billion in capital for the transit system’s expansion to the San /Francisco Airport along with seismic retrofit and other rehab programs.

It was a turbulent time, and Richard was in the middle of a BART strike, a bankruptcy, and a state energy crisis while at the same time playing a pivotal role in BART’s extension to the San Francisco Airport, in itself a major undertaking that was successfully completed10 years ago.

“The airport extension animates much of my thinking on high speed rail because it contained many of the same issues and challenges we face on this project,” says Richard. “An integral part of the effort was putting together a funding package to revitalize the system with new equipment and a seismic retrofit, a major effort in itself.”

Richard met Jerry Brown during his first term as governor when he was the state’s deputy assistant for Science and Technology in 1978, following his boss, former astronaut Rusty Schweickart, who’d become assistant for the same function. In 1982, he again followed Schweickart as advisor to the Chairman of the California Energy Commission.

Richard served Brown as his Deputy Legal Affairs Secretary in1982-83 before leaving to enter the energy consulting business where he remained for the next 15 years.

In1992, Richard embarked on a dual track career, winning election to the Board of the Bay Area Rapid Transit system, one of only four such systems in the nation with an elected board. He also attracted the attention of Pacific Gas & Electric which was struggling with the deregulation of the electric industry and, in 1998, joined the company as a Senior Vice President in charge of all regulatory, government and community affairs.

Richard was on the BART Board until 2004 and retired from PG&E in 2006. “Then I started a new infrastructure finance business which was not successful because we couldn’t raise the funds needed, but one often learns from unsuccessful efforts and there are things from that effort that have provided me with valuable tools,” he says.

Brown called in him in 2010 after winning the election. “I’d been living both in Piedmont and Washington D. C. since my wife was working in the Energy Department for the Obama Administration, but she resigned and we’ve resituated in Piedmont,” Richard recalled.

—

Ed’s Note: Jim Cameron is a regular contributor to Capitol Weekly.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

One wonders if one of the “valuable tools” Richard learned from his brief excursion into the private sector was that the public sector projects are a whole lot easier and safer to pull for than private ones.