News

Where are they Now? Pat Nolan

Pat Nolan addresses a 2014 meeting of CPAC <(Photo: Gage Skidmore)

Pat Nolan addresses a 2014 meeting of CPAC <(Photo: Gage Skidmore)Pat Nolan has Southern California credentials that are about as solid as they come.

The future Assembly Republican leader was born into a family that had been in the area for generations. One of his great-grandfathers had been an early settler of the area for whom two cities (Agoura and Agoura Hills) are named. He grew up in a large family in Los Angeles and Burbank, and after high school attended the University of Southern California. Although his was not an overly political family, he was inspired by Gov. Reagan and worked on a number of campaigns.

“I think it was the right time to run. I was single at the time and able to devote myself to policy in the Legislature.” — Pat Nolan

Nolan also played a role in one of the Capitol’s darkest episodes – the federal investigation of corruption in the 1980s and 1990s. More about that later.

In 1978, a few years after graduating and starting a career in law, his Assemblyman, Mike Antonovich, decided to run for lieutenant governor rather than seek a fourth term. As a well-connected conservative, Nolan began to think about running.

“Do I leave my legal career?” he asked himself. In the end, he realized that if he never ran for office, it would likely be a major regret and that this was a great opportunity. “I don’t want to be fifty with three kids and a dog and wish I’d run for office. I think it was the right time to run. I was single at the time and able to devote myself to policy in the Legislature.”

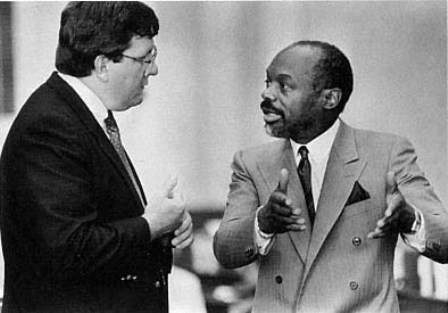

Pat Nolan, left, and Willie Brown, 1986. (AP/Rich Pedroncelli)

At campaign events, one question came up repeatedly.

“During the campaign, people would ask ‘Are you a family man?'” He delivers the punchline with laughter in his voice: “Yeah, I have eight brothers and sisters!”

Looking back, Nolan, 67, says that as a young candidate he didn’t understand the significance of the question and what the voters were actually saying, “Do you understand how precious these children are? I would do anything to help my children prosper and flourish. I don’t think it would have changed any of my policies, but I lacked understanding. Your perspective on life changes when you hold your first child in your arms.”

He won the November 1978 election with more than two-thirds of the vote. The Republican class of ’78 later became known as the “Prop. 13 babies” and the “Cavemen” for their strong anti-tax positions. Voters approved Proposition 13 that same year.

As soon as the meeting started, “this fellow jumped up so fast that he kicked over his chair and nominated Paul Priolo for leader.”

Almost immediately after an election, newly elected members are flown to Sacramento for a caucus meeting to vote on the selection of the party’s leadership.

“On a PSA [Pacific Southwest Airlines] flight, we were flying up for caucus, one of my new colleagues was railing against [Assembly Minority Leader Paul] Priolo and the caucus.” As a new member, Nolan was surprised at the intensity of the attack on the Republican leader.

Arriving in Sacramento, the legislators were taken to a restaurant where the meeting was to be held. As the meeting began, Nolan was surprised to see this same colleague, who has spent the flight north bashing Priolo, have a sudden change of heart. As soon as the meeting started, “this fellow jumped up so fast that he kicked over his chair and nominated Paul Priolo for leader.”

As the second-youngest member of the freshman class, Pat recalls the experience of being a new member as one of joy, although there were some tensions within the caucus. “There was a lot of camaraderie in our class, and frankly we were resentful of the older members of the Republican caucus who liked our votes but didn’t listen to us.”

A few months later, Nolan had another experience that gave him insight into how politics actually worked.

“At one point when we were voting on the budget, we had a caucus and I gave an impassioned speech,” he said. As the caucus broke, the members began the slow walk back to the floor. A senior Republican standing nearby put his arm around Nolan, pulling him in, and asked “You believed that shit, didn’t you?”

“Some people run for elected office just to hold office,” Nolan said. “It wouldn’t have been worthwhile to just hold office.”

The Agent Orange bill faced a great deal of opposition from both the Veterans Administration and Dow Chemical because at that point, so soon after the end of the war

Years later, as Assembly Minority Leader, Nolan would talk to people interested in running for the Legislature. During these conversations, his goal was to determine whether they were seeking elected office in order to just hold elected office or it if was to actually make a change.

“I’d interview candidates and seventy to eighty percent of them would say, ‘I’ve always wanted to serve the public.’” If Nolan was lucky, he would find those rare outliers who wanted to make a difference. “Twenty percent would say ‘I’m mad about taxation or abortion.’ They wanted to hold office as a means to accomplish something.”

One of his proudest moments as a legislator was tackling veterans’ health issues, which was even then a highly contentious issue.

“When it was still controversial, I carried a bill to create a registry to track Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange.” Nolan says that the bill faced a great deal of opposition from both the Veterans Administration and Dow Chemical because at that point, so soon after the end of the war, there was a lot of opposition to even the possibility that the United States had harmed its own soldiers.

Nolan also authored the legislation to establish enterprise zones, which gave tax breaks to businesses that established themselves in low-income communities.

The meeting ended with Nolan leaving with two checks — one made out to a campaign committee and another that was deposited into a PAC account.

It wasn’t just the tax benefits that helped. Nolan inserted a requirement that cities that wanted to establish enterprise zones had to set up a one-stop-shop, making it easier for quicker processing of businesses applications. “We wanted the small businesses to flourish,” he says “We were able to build bridges and work together.”

A decade into his time as a legislator, Nolan had a life-changing conversation. At the time, it probably seemed like just another of the 15-minute meetings that caucus leaders have nearly every day: Someone had come to Sacramento to ask if there was anything he could do to help with the passage of a bill.

At some point in the conversation, Nolan mentioned in general terms that Republicans were generally more business-friendly than Democrats, and that having more of them in the Legislature couldn’t hurt. The meeting ended with Nolan leaving with two checks — one made out to a campaign committee and another that was deposited into a PAC account.

Every new staffer in the Capitol is told at some point to avoid conversations that mention both legislation and money. Sitting at your desk, you can talk about legislation and votes all day. Alternatively, you can step outside the Capitol and talk campaigns and contributions for as long as you can find someone to talk to.

But the instant a caller tries to connect the two (“I love how your boss voted! Where do I send my check?”), you end the conversation — fast.

All other charges would be dropped if he pleaded guilty to a single count of racketeering and he could be out in less than three years.

Pat Nolan hadn’t explicitly offered to push the legislation in exchange for money, but both topics had definitely been raised during the 20-minute conversation. He wasn’t a new legislator, and his years of experience as an attorney gave him a better understanding of the law than most. Speaking to him recently, it’s clear that even now he doesn’t think that he got anywhere near the legal line.

Unfortunately for Nolan, the person he met with was an undercover FBI agent pretending to be a businessman. The agent was investigating corruption at the Capitol, and Nolan now was on tape accepting what the federal government argued was a bribe.

In 1993, Nolan was charged with seven counts, including racketeering and extortion, and he was faced with a terrible choice.

If he fought the charges, there was a chance that his attorney could prove that he hadn’t accepted an illegal payment and he’d be free. Alternatively, if he was found guilty, he’d potentially face decades in prison; “Roll the dice hoping to be exonerated or lose the trial and face to the trial penalty. The maxed-out sentence would have been 21-plus years.”

Perhaps as a reflection of the strength of the case, the prosecutor offered Nolan a plea deal: All other charges would be dropped if he pleaded guilty to a single count of racketeering and he could be out in less than three years.

For Pat Nolan, the decision between fighting to clear his name and cutting his losses came down to family. Nolan had three young children at home and he realized that they would be well into adulthood by the time he got out if he lost. “The biggest thing was my family,” he says today, “The reason I lied and said I did something I didn’t do was my family. I would have missed their entire childhood… My family came first.”

Nolan took the plea deal.

Arriving in prison is a difficult transition for anyone, but it’s hard to imagine a larger transition than going from lawmaker to inmate. For Nolan, it also marked a journey to a religious transformation.

At his first prison, in Northern California, Nolan was named the prison’s law librarian because of his experience as an attorney and lawmaker.

“Obviously there was a culture shock,” says Nolan. In his attempts to understand public safety as a legislator, Nolan had toured a number of state prisons over the years. Now, as an inmate, he got to see the other side of what he described as a Potemkin village.

At his first prison, in Northern California, Nolan was named the prison’s law librarian because of his experience as an attorney and lawmaker. Exploring the room, Nolan found a room filled with what appeared to be a vast collection of law books. A closer inspection of the wall of matching red, black and tan law books revealed that they were copies of the Atlantic Reporter, a publication that reports on East Coast cases.

“It looks very impressive to visitors but is useless to inmates” said Nolan.

Soon after, the head of the Bureau of Prisons arrived for a tour. In the days leading up to the visit, new palm trees were planted outside the main gate and fresh uniforms were issued to the inmates. A large new coffee urn arrived, but was installed in a location without a water connection or an electrical outlet. For all the promises, not a cup was ever poured. And within weeks, the new uniforms were collected, the old ones redistributed and the palm trees, now dead, had been removed.

“God has a purpose in everything,” Nolan said, reflecting on his experiences, “He doesn’t will bad things to happen. He opened my eyes in prison, even during the prosecution, that government is very powerful. You have nowhere near the resources that they do. In prison, I saw all these young people who didn’t have a chance. They may have been abused, lived on the street, or been involved in drugs and gangs.”

“I would think that even an atheist warden would want religious programs. I thought they’d encourage it, but they don’t.” — Pat Nolan

As hard as their lives had been, there was little chance for a better future. “Nothing was being done to prepare them for staying on the straight and narrow once they got out.”

Released from prison in 1996, Nolan was hired by Prison Fellowship Ministries, which had been founded in 1976 by Chuck Colson, who had served time for obstructing justice during the Watergate scandal. At Prison Fellowship, Nolan’s goal was to expand the use of religious programs to rehabilitate inmates by using tools that secular government programs can’t.

“I would think that even an atheist warden would want religious programs,” explained Nolan, arguing that it’s helpful for inmates to understand that they’re not the center of the universe, “I thought they’d encourage it, but they don’t.”

A little over a decade ago, Nolan received a phone call that once again changed the direction of his life.

Over the years, Pat has maintained regular contact with Jared as he married Ivanka Trump in 2009 and more recently became senior adviser to his father-in-law, President Donald Trump.

On the phone was Gary Bauer, a former Reagan administration official and 2000 presidential candidate. “There’s a family, the father is going to prison,” he told Nolan. They need help.

After a decade at Prison Ministries, this was nothing new for Nolan. “I’ve done the same thing for families that have lost everything,” explains Nolan, “My pain going through the prosecution can help others. I’m passive and God’s using me.”

The man preparing for prison was Charles Kushner, an East Coast real estate investor and major Democratic political fundraiser, who had recently pled guilty to more than a dozen federal charges.

“I didn’t know he was a rich real estate guy. Among those in the family that Pat became close to was Kushner’s oldest son Jared. Over the years, Pat has maintained regular contact with Jared as he married Ivanka Trump in 2009 and more recently became senior advisor to his father-in-law, President Donald Trump.

Since January, Nolan has been a guest at the White House several times. He’s also currently working with Congress to change the way that wardens are evaluated. His proposal is to require each warden to report the number of times that volunteers visit each year, what programs are active, how many inmates are participating, and how many have finished the programs.

He also spends time on the great American pastime of television-watching. His favorite shows? “I enjoy watching Law and Order,” he said with a laugh.

“Grade and promote wardens on the safety of the public. Evaluate them on recidivism; that’s public safety.” Nolan argues that this would incentivize wardens to not merely keep prisoners locked up, but proactively work to turn prisoner lives around.

One thing about Pat Nolan that has remained consistent since his first election to the Assembly nearly forty years ago is his love of reading. Asked how he spends his free time, he mentions three books that he’s currently reading in addition to his efforts to stay up to date on the latest research. Two of the books that he’s working on (Alliance of Enemies by Agostino von Hassell and Church of Spies by Mark Riebling) are about the spy networks and backroom deals that tried to limit the Nazi advance during World War II.

He also spends time on the great American pastime of television-watching. His favorite shows? “I enjoy watching Law and Order,” said Nolan with a laugh.

Having spent fifteen years in the state Assembly, Nolan also occasionally spends time keeping up to date on California politics. He says that the two decades of term limits had significantly changed the Legislature, which he had seen the beginnings of during his final years.

“Rather than being citizen legislators, everyone arrives looking for where they can land next,” said Nolan. “They plan to be in office, just not enough to care what happens.”

In the past few years, the new term limits law has given him a reason to hope for better days in the Legislature’s future. Having longer to stay in office, Nolan hopes that they will make the decision to stay put.

“You want them to have a good head, but even the best need to also know about the rules,” he says.

“Somebody needs to stay and tend the store.”

—

Ed’s Note: Alex Vassar, often referred to as the “unofficial historian of the Legislature,” is a state worker and the author of “California Lawmaker.”

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Good story about a great guy.