News

In world of stem cell research, ‘UC Caucus’ reigns supreme

Mesenchymal stem cells are injected into the knee of a patient. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons photo, via VT Digger)

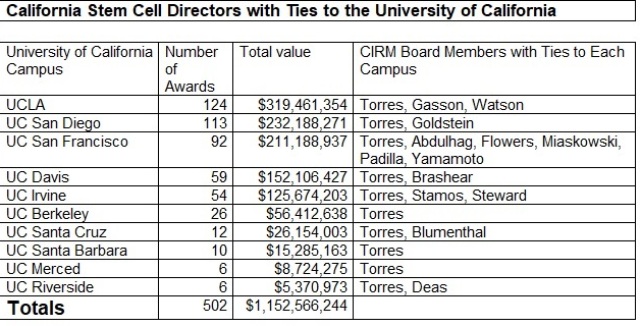

Mesenchymal stem cells are injected into the knee of a patient. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons photo, via VT Digger)They could be called the “UC Caucus,” although that may presume too much. Nonetheless, they come from an institution that has pulled down $1.2 billion from the California state stem cell agency, more than any other enterprise during the last 16 years.

Not to mention that their employer — the University of California — is likely to snag much, much more during the next decade or so.

The “caucus” is composed of the 13 persons with ties to the University of California (UC) who are also members of the governing board of the state’s $12 billion stem cell agency, known officially as the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine(CIRM).

The board is so large, in fact, that at times its board members have outnumbered the CIRM staff.

The UC 13 constitute the largest voting bloc on the CIRM governing board. The “caucus” includes Art Torres, who is a member of the UC Board of Regents and the salaried, vice chairman of the CIRM board of directors. Torres is a well-seasoned, former state politician with decades of vote-counting experience.

The CIRM board is much larger than your usual corporate board. With 35 members, it approaches the size of the 40-member California State Senate where Torres served 12 of his 20 years as a state legislator. The board is so large, in fact, that at times its board members have outnumbered the CIRM staff.

The board is the ultimate legal arbiter of who and what enterprises and programs receive the billions in CIRM cash. A subset of CIRM directors makes the formal decisions on awards, excluding those who have direct conflicts of interest involving an application. But the full board establishes the rules of the game and votes on such questions as:

–Should more millions go for basic research as opposed to clinical work that is closer to bringing a therapy to the public and to the marketplace?

–Are matching millions to be required from applicants?

–Do supplicant scientists have to meet milestones and comply with new, more rigorous diversity standards?

–Should CIRM create a special program to seek cures for sickle cell disease or Alzheimer’s or diabetes?

–Should the state of California require large royalties for treatments developed with taxpayer funds?

–What types of stem cell or gene therapy can be supported?

–What will be the standards for a new $82.5 million building plan which could benefit UC campuses?

All those questions and many more involve the CIRM board, which is officially called the Independent Citizens Oversight Committee (ICOC), a politically appealing phrase that is more voter friendly than “board of directors.” Those who drafted the ballot initiative that created CIRM had a keen eye for what would work well with voters.

The issues do not always surface in an unambiguous fashion.

Campaign tactics aside, the CIRM board is dominated by persons whose enterprises have something to gain from its actions, whether it is a stronger focus on a particular disease area or research buildings that have been built with the help of hundreds of millions of dollars in taxpayer cash.

Independence, of course, can be in the eye of the beholder. But the 13 UC members are a good example of how the interlinking ties work and sometimes create touchy issues in the blended world of academic research and commercial production of stem cell therapies that could cost $1 million and more.

The issues do not always surface in an unambiguous fashion. But one clear example of the interplay surfaced in a $262 million round. It involved not research, but generous grants to build new facilities. Sherry Lansing, a former chair of the UC Board of Regents and then a member of the CIRM board, in 2007 felt compelled to remove herself from the process.

She had been named as a member of the CIRM’s directors’ committee that was devising the rules and standards for the round. But at a July 12, 2007, meeting of the group then ICOC Chairman Robert Klein announced that he had spoken with Lansing by phone and that she was resigning from the group. Klein said “she was concerned too that since she’s on the UC Regents, she has conflicts in a number of institutions….”

The University of California-CIRM nexus surfaced more recently in the case of the Orchard Therapeutics bubble baby saga, which remains to be fully resolved. That story involves $42 million supplied via CIRM’s money pipeline, research at UCLA, intellectual property belonging to the University of California and an exclusive license issued to Orchard.

Art Torres could be called the putative head of the UC caucus. He is the part-time, salaried ($225,000 as of 2020) vice chairman of the ICOC.

The license from the University of California centers on a highly successful product called OTL-101, a type of gene and stem cell treatment. It has saved the lives of more than 50 children suffering from the rare bubble baby disease (ADA-SCID), according to UCLA. However, Orchard, which is publicly traded, decided to abandon the treatment in favor of ones that had more promise of profits. It also declined to provide for compassionate use of the treatment by 20 children.

The Orchard episode raised questions about how the University of California and CIRM are going to deal with the ethical and intellectual property issues surrounding curative treatments such as gene therapies, which still are very new on the biomedical scene.

One scientist familiar with the situation, who requested anonymity to speak frankly, told the California Stem Cell Report last month that the situation with Orchard involves “a socialized research process and privatized profit, and profit shouldn’t be the sole consideration when someone actually comes up with a cure.”

-0-

Art Torres could be called the putative head of the UC caucus. He is the part-time, salaried ($225,000 as of 2020) vice chairman of the ICOC. Torres is also a member of the UC board of regents and the board of Covered California, a state agency that helps with affordability issues involving health insurance. Torres chairs the board’s new and still embryonic affordability and accessibility program authorized by Proposition 14 and funded with as much as $155 million.

Torres has a decades-long history as a powerful California politician, a background he often mentions at ICOC meetings. His guidance was deeply influential in leading the CIRM board to support a ballot initiative to refinance CIRM with $5.5 billion last fall rather than going directly to the Legislature. The agency was created with $3 billion in funding, but that was gone by last year.

Torres currently also serves on the board’s six subcommittees, including the one that evaluates the performance of CIRM CEO Maria Millan. Recently, he was added to the communications and intellectual property panels.

To be sure, some of the 13 are quite new appointees to the CIRM board.

The other members of UC caucus range from the former chancellor of UC Santa Cruz to a professor of family medicine at UCSF’s Fresno site. UCSF is a medical research powerhouse. It is the only institution that has five representatives on CIRM’s “independent” governing board, putting aside UC’s 13.

Sources: California Stem Cell Report, CIRM as of June 16, 2021

In addition to Torres, the UC-connected members of the CIRM board are:

—Haifaa Abdulhaq — a professor at the Fresno site for UC San Francisco and director of hematology at Fresno

—George Blumenthal — former chancellor of UC Santa Cruz

—Allison Brashear — dean of the medical school at UC Davis

–Deborah Deas — dean of the medical school at UC Riverside

—Elena Flowers — associate professor of nursing UC San Francisco

—Judith C. Gasson — director of the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCLA

—Larry Goldstein — professor at UC San Diego, a past recipient of $22 million in CIRM funding and “senior advisor for stem cell research and policy to the UC San Diego vice chancellor of health sciences”

—Christine Miaskowski — professor of nursing at UC San Francisco, co-director of the Pain and Addiction Research Center at UCSF

—Adriana Padilla — clinical professor of family medicine at Fresno site of UC San Francisco

—Michael J. Stamos — dean of the medical school at UC Irvine

—Oswald Steward — director of the Reeve-Irvine Research Center at UC Irvine

—Karol E. Watson — professor at the UCLA medical school

—Keith R. Yamamoto — vice chancellor for science policy and strategy at the UCSF medical school

To be sure, some of the 13 are quite new appointees to the CIRM board. The group has never been known to meet together as a caucus and probably never will. Such an action could lead to problems associated with the state’s opening meeting laws.

The 13 also have diverse personal and professional interests that mitigate against acting in concert on matters involving UC. Their appointing authorities also vary significantly as do the qualifications to serve on the CIRM board..

The amount received collectively by UC from CIRM is not necessarily out of line, given the number of campuses and their importance in conducting stem cell research. The ballot measure that created CIRM additionally gave all the major California players a seat at the table where the cash was handed out, an obvious political move to win support. Stanford University ($386 million in CIRM awards) has a seat. So does the City of Hope ($126 million in awards) and so forth.

The UC largess does renew attention to complaints dating back to 2004 that CIRM should not be overseen by those who actually stand to benefit from its billions. That was an important issue in the 2004 campaign that created CIRM, but it was overshadowed by the promise of miraculous stem cell cures.

Last month the California Stem Cell Report queried all of the UC 13 about the fallout from Orchard and its implications for the future. The questions involved such things as:

–Do you think that the University of California should re-examine its licensing practices dealing with curative treatments, genetic or otherwise, produced at UC? It seems that the science is outpacing UC’s policies and ethical considerations.

–Do you think CIRM and/or the University of California should promptly begin a reassessment of its standards and intellectual property regulations?

Not one of them replied, including Torres. One can only speculate about the reasons for their silence on what is a significant ethical and financial matter that is likely to become more important as gene therapy advances with its promise of one-off, actual cures. The silence of the UC 13 may reflect, at least in part, a recognition that they are fully aware of their dual roles and how they are trying to carefully straddle a gap that involves two responsibilities, two obligations and two masters.

Editor’s Note: David Jensen is a retired newsman who has followed the affairs of the $12 billion California stem cell agency since 2005 via his blog, the California Stem Cell Report. His recently published book, “California’s Great Stem Cell Experiment,” explores the pluses and minuses of the agency’s work.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply