News

Coronavirus and authors: Book promotions in CA take a hit

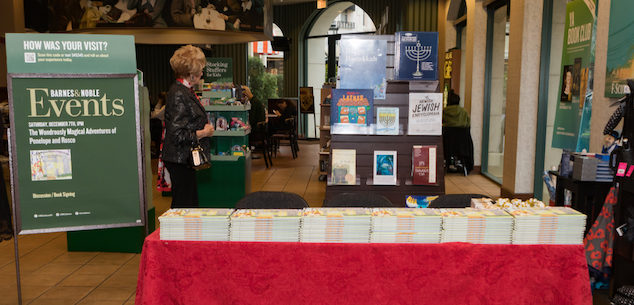

The setting for a book-signing event at a Calabasas bookstore, just before the pandemic hit. (Photo: Jesse Watrous, via Shutterstock)

The setting for a book-signing event at a Calabasas bookstore, just before the pandemic hit. (Photo: Jesse Watrous, via Shutterstock)On Tuesday March 17, the nation’s first effective coronavirus shelter-in-place order took effect in California. At midnight, non-essential businesses in six San Francisco Bay Area counties – from salons to bookstores – closed. As Pete Mulvihill, co-owner of Green Apple Books, told KQED about the order, “We haven’t closed since the 1989 earthquake and that was only one day.”

Some California bookstores were proactive and closed before the order, including Point Reyes Books, in Marin County, which willingly closed on March 16, after a day of near-record sales. Many, like Booksmith, City Lights, and East Bay Booksellers, worked to bulk up online sales and offer curbside pickup in place of browsing.

Books published in March and April were especially hard hit, because their authors suddenly could not engage with readers in-person as they usually would.

“The rural stores,” says Calvin Crosby, Executive Director of the California Independent Booksellers Alliance, “some of which were deemed necessary by their municipality, city or county, were as proactive [as city stores] but could dive into store pickup, or even controlled browsing, in a way the concentrated population areas could not.”

Along with browsing and buying, the book industry struggled to replicate the in-store, in-person events that authors have traditionally used to promote their new books. Books published in March and April were especially hard hit, because their authors suddenly could not engage with readers in-person as they usually would. The entire industry was forced to do what everyone from piano teachers to newlyweds were doing: take their events online.

Alternately known as readings, author events, and publicity events, these in-store, in-person readings have a basic formula: authors read selections from their new books, or do an on-stage interview, then answer questions from the audience, in the hopes of selling copies, driving store sales, building community, and building their brand. Traditional in-store events put readers in a physical context where they might buy newly released books. Closures meant authors promoting books had little choice but go online.

“Right now, most publishers’ approach seems to be ‘We are going to try everything…’” — Ethan Nosowsky,

As San Francisco based author Marie Mutsuki Mockett says, “There really were no alternatives that anyone thought of.” Her most recent book American Harvest published on April 7, which was the first proposed end date of the Bay Area shelter-in-place order. Gov. Newson extended the order to May 3.

“We don’t have a choice,” she said. “There is no point in fighting what is happening. We have to make this situation work for us, as writers, artists, thinkers, booksellers, publications, and audiences.”

“Right now,” says Graywolf Press’ Executive Director Ethan Nosowsky, “most publishers’ approach seems to be ‘We are going to try everything,’ to the extent that our authors have the energy to keep trying different formats, see what works, what authors do and don’t like, see what helps and doesn’t help book sales.”

Founded in Port Townsend, Washington in 1974, Graywolf is now based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Nosowsky, a Bay Area native, works for the press remotely from Oakland. Graywolf only publishes a few books per month, and American Harvest was one of the approximately half dozen spring titles affected by California bookstore closures. Mockett has never seen her new book in a store, and she hasn’t done a California based event, only online events.

Besides attendance, one practical problem that publishers are trying to solve is how to encourage readers to buy books at a virtual event.

The industry is still monitoring the transition from in-store to digital events, and trying to measure online readings’ success, improve audience and author satisfaction, and shape the future of book promotion.

How it works

COVID changed everyone’s sense of normalcy around digital social interaction. Office workers are now in Zoom meetings much of the day. Kids are in Zoom meetings for school. There is certainly some screen burnout. The last thing some people might want to do is get on another Zoom meeting at 5 o’clock for an author event. But now that we’re used to attending activities on screens that we never imagined doing online, such as happy hours and weddings, readers have become more receptive to attending an online author event.

“I don’t know if it’s going to be an ongoing way we live our lives,” says Nosowsky. “For now, people seem open. I’ve seen some pretty high attendances for some of our author events.”

Besides attendance, one practical problem that publishers are trying to solve is how to encourage readers to buy books at a virtual event. It’s a different experience when readers are browsing a store, where the featured book is there to pick up off a beautiful display after hearing an author speak.

Online events are also opportunities to reinvent an old industry standard that was inherently imperfect…

Authors have been using several platforms, including Zoom and Crowdcast. Zoom doesn’t provide viewers with a buy link, so even at Zoom events with high attendance, publishers can’t tell if any books sold. Crowdcast provides a buy link in the video screen and lets publishers track very concretely who bought a book during or after an event. Publishers are still collecting data to see if attendees are actually buying books

But for many mission-driven, nonprofit publishers like Graywolf and Heyday in Berkeley, events also try to get readers to engage with the ideas in the book. “The literary end of book publishing has always walked the line between art and commerce,” says Nosowsky. “We want to sell as many books as we can, but the broader goal is to publish books in a way that contributes to a broader cultural conversation.”

Benefits of digital events

It’s easy to see digital author events as a fast fix for the loss of conventional events, even a form of damage control, since the world changed so quickly that authors and publishers had to quickly construct alternatives. But online events are also opportunities to reinvent an old industry standard that was inherently imperfect, and to improve the way authors promote books and readers engage with authors in California and beyond.

Some digital events have very active chat boxes, where attendees feel comfortable typing questions for the authors, possibly more comfortable than asking in a store during events’ Q&A portions. Digital events also provide an opportunity to reach readers in rural areas and international readers.

This early stage of digital book promotion is an ongoing experiment, where everyone is trying things out, collecting data, and figuring out best practices for authors so events can be streamlined and made more effective.

Even before COVID, measuring in-store events’ success has always been abstract. The number of books sold was never the absolute measure of how an event or book tour went.

If a store sells thirty books or 5 books, what’s reasonable for a digital event?

“As any author who has gone on a book tour over the last twenty years can tell you,” says Nosowsky, “if you do a bunch of events, you very well may go to a bookstore where three people show up for the event. So then you can say, ‘Well that was a waste,’ in terms of attendance and sales. But the other measure is you got to meet the booksellers at that store. And in two weeks, that bookseller might have somebody walk into their store looking for a new book, and they might say, ‘Oh, we just had this author in the store, and they were wonderful, their book is fantastic, and do you want to buy it?’ What happens at the actual event is not necessarily the very end of that interaction.”

Publishers are nearing the end of their first batch of virtual book tours, so they will have more sales figures to assess their effectiveness in fall. For now, they have little baseline for comparison: If a store sells thirty books or 5 books, what’s reasonable for a digital event? Similarly, the hope is that a digital event’s effectiveness will go beyond sales.

Author experiences & celebrating in public

It’s easy to focus on sales, audience engagement, and the technical kinks of this new format. But the author’s experience is another piece of this puzzle.

Creating a book is a gargantuan task. Marie Mutsuki Mockett is the author of three books, both fiction and nonfiction. Measured from her first inkling on the back burner of her mind in 2005, American Harvest took 15 years to write, going through many years’ worth of research, field reporting, drafting, multiple rounds of major revisions and edits, leading to a near-final draft around May 2019.

It’s easy to think of publication as the final stage in a book’s life: the act of getting the story out of the author’s mind and into readers’ hands.

“We thought we were going to be publishing this book into a crowded election season and nomination process,” says Nosowsky, who edited American Harvest. “We did not anticipate a pandemic and major civil unrest. She was incredibly energetic and adaptable, so it really helped. But when her book landed, bookstores were completely shuttering and struggling to adjust their online operations. That came together in a few weeks. It was a very challenging environment to publish a book in.”

Numerous book festivals, including The Bay Area Book Festival in Berkeley, and The Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, canceled because of COVID.

“These were huge, essential ways to bring the public into a space where they could discover authors and see authors speak,” says Nosowksy. “The festivals are also trying to reinvent themselves.”Mockett and Graywolf had to rethink promotion very quickly. “She did do a lot of online events,” says Nosowsky, “and wrote a lot of articles. Publishing is tough in the best of circumstances, and she met that with great energy and grace.”

Many writers have certain hopes and expectations for the final stage of their book’s lives: not just good reviews, but the opportunity to present their work to receptive readers in person, and to celebrate the book’s physical existence.

It’s easy to think of publication as the final stage in a book’s life: the act of getting the story out of the author’s mind and into readers’ hands. But author events lie closer to the final stage, because these public gatherings function as a kind of celebration, and a way for the author to ceremonially hand their book off to the public to do with it, and assess it, as they will.

“I lost all my in-person events, and they were going to be, for me, a turning point in how I think of my career.” — Marie Mutsuki Mockett

Writing and reading are solitary endeavors. Book releases are a rare group experience in the literary sphere. A book is also historically a physical thing. It goes into readers’ hands before it goes into their minds. The communal, relational aspect of an author event is gratifying. At events, authors can see reactions in readers’ reactions. They can talk about the story, ideas, and the reading experience together. With that in mind, it is difficult to digitally replicate that tactile, group experience. Where publishers and California bookstores have to contend with the financial implications of online promotional activity, authors struggle with the loss of personally engaging with readers. After years of quiet labor, publishing a book without reading it to a bookstore audience can seem anticlimactic.

“I lost all my in-person events,” says Mockett, “and they were going to be, for me, a turning point in how I think of my career. I was finally going to be a featured speaker! These events all disappeared; it has, at times, been very hard to take. I badly wanted to be in conversation with Jess Row at AWP. I badly wanted to be in conversation with Pico Iyer at the Bay Area Book Festival. I badly wanted to be in conversation with Lyz Lenz at the LA Times Book Festival.”

While promoting online during COVID, publishers also have to leave their authors room to mourn and feel disappointment, too. “Digital events are not the same,” says Nosowsky, “and I don’t want to pretend they’re the same.”

“The best way for me to cope has been to let this book go and start new projects,” says Mockett. “I’m trying to retain my best sense of self, knowing that in the grand scheme of things I am fortunate.”

The future

So many people still talk about returning to so-called normal life after COVID. This is true in the literary world, too, this idea that once this pandemic ends, audiences can return to their seats in bookstores for their usual programing. But digital events offer enough novel benefits that authors might not simply want to abandon them after the pandemic. Maybe there are elements of the online reading that they will want to keep in future promotional plans, or possibly integrate into in-store events.

“We really depend on events to drive sales. Virtual events, no matter how good, are hard to monetize — Adrian Newell

“I think there are possibilities for digital events to fill in some holes that a conventional book tour leaves open,” says Nosowsky. “Any work that we’re doing now to think about how to make digital events more effective will not be wasted.”

COVID will likely change our lives and California forever. Digital events will likely change the publishing landscape, too.

“It used to be that only handful of authors got book tours,” says Nosowsky, “or went on elaborate lengthy book tours, but now, at no cost to the publisher, any author can be on book tour. That means it’s also going to be a lot more competitive to get events at the bigger book stores, because literally now anybody is accessible to them to host, so I think there’s going to be more authors trying to do digital events. That will make it harder to find channels they can stick to.”

Some stores are already experimenting with in-store events again.

When Elin Hilderbrand’s new novel 28 Summers came out on June 16, she did what few authors had since the pandemic hit: she did in-store book events, including one at Warwick’s in San Diego, on Friday June 26. Warwick’s wasn’t technically “in-store.” It was held outdoors.

“We really depend on events to drive sales,” Adrian Newell, Warwick’s head book buyer, told Publisher’s Weekly. “Virtual events, no matter how good, are hard to monetize — even when we make people buy a ticket to enter the event online, lots of people will just watch the archived event later. So, we’re really hoping we can find a way to make live, in-person events work, provided we can ensure everyone’s health and safety.”

—

Editor’s Note: Aaron Gilbreath is an author and free-lance writer who explores unusual topics related to California and its politics.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply