Analysis

Progressives felt in deep-blue California

Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer and several fellow Democrats at the state Capitol. i>(Photo: State Assembly)

Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer and several fellow Democrats at the state Capitol. i>(Photo: State Assembly)Meet the progressives, an outgrowth of California’s Democratic political landscape.

As Democrats began their dominance in California over 20 years, they saw their electoral success expand out of urban centers into wealthier suburban enclaves, such as Pasadena, Calabasas, and Walnut Creek.

With this change came the New Democrats, a name brought to fame by former President Bill Clinton. These were Democrats who supported workers, and social and civil rights, but who were attuned to business interests, businesses that provided jobs and commerce for communities. These policies often clash with labor, environmental, and consumer interests, but allowed for expansion of Democratic elected officials in the suburbs.

“We had several meetings to formulate what it should be and one day Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher said let’s get a list and just do it and ask people of they want to be a member.” — Reggie Jones-Sawyer.

Without a strong Republican Party in California and because of the sheer size of the Democratic Party, moderates began to coalesce, while business interests built bridges and supported moderate, business-friendly Democrats.

The moderates have had a loosely formed group for years, but the progressives have not.

But all that changed earlier this summer when Assemblymembers Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles) and Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher (D-San Diego), both considered progressives, started recruiting members. A “progressive” is commonly viewed as a person who seeks social reform and advocates liberal ideas.

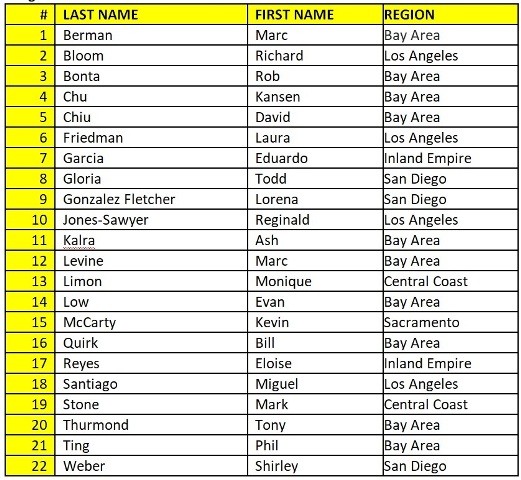

“We had several meetings to formulate what it should be and one day Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher said let’s get a list and just do it and ask people of they want to be a member,” said Jones-Sawyer. “Less than three hours we had the list we have now. We have 22 members. I think it’s up to about 35 members because if you look at voting records you would characterize more members as progressive.”

“We put these labels on legislators, but I’m not sure we have a universal definition of what the label means.” — Monique Limón.

One of the recruits, Assemblymember Monique Limón (D-Santa Barbara), had received blanket criticism over the death of single-payer health care legislation in the Assembly. She and other progressives felt they needed to come together as a group and show their voting records are in fact progressive.

The emerging progressives appear to be part of California’s tribal, four-party political landscape – the Establishment Republicans, the Hard-Right Republicans, the Establishment Democrats and the Progressive Democrats (also known as the “Berniecrats”).

“We put these labels on legislators, but I’m not sure we have a universal definition of what the label means,” said Limón. “In Sacramento folks put us in boxes and labels, but that isn’t always consistent with what the district sees. I consider myself a progressive.”

Jones-Sawyer is the convener of the group and contends the progressives will decide before the next legislative session whether to stay a loosely formed group, like the Moderate Democrats, or form a more structured caucus.

“I have a feeling we are going to be less bureaucratic and organizational,” said Jones-Sawyer, similar to the structure of the Moderate Democrats.

For progressive groups outside of the Capitol, the group’s formation may not change business much, but it could allow for new opportunities.

The formation of the caucus did not necessarily come from trying to rein in power from moderates, or flex muscle. The number of progressives in the Assembly is quite large. Currently, there are 22 members. Not surprisingly, about half of them are from the Bay Area.

Listing provided by Reggie Jones-Sawyer

If Jones-Sawyer’s estimate is accurate — nearly three dozen members who are interested in, or sympathetic to, the progressive cause – the progressives would be arguably the largest sub-group in the Assembly after the Democrats overall, who run the 80-member house – 55 Democrats, 24 Republicans and one vacancy.

One of the arguments to keep the group less structured is that it allows for a larger working group not bound by ideology that effectively turns legislation into laws.

“There are checks and balances, we all work to get the best legislation we can. For me I would rather have a bill that helps African Americans, Latinos, the disadvantaged, women’s rights, that gets 90% of what I want,” Jones Sawyer said.

For progressive groups outside of the Capitol, the group’s formation may not change business much, but it could allow for new opportunities.

“I don’t think it changes how we operate, because we know who our friends are and we would be talking to them anyway,” said Kathryn Phillips, director of Sierra Club California. “Maybe at the most there will be opportunities to talk to all of them together.”

In agreement with Jones-Sawyer and Limon, Phillips says that even among progressives, interest groups cannot always depend on their ideological allies all the time. Every legislator is different with a unique interests, beliefs, and districts.

“There are varying degrees of work we have to do have to help members vote in the way we think is consistent with environmental values,” said Phillips. “Just because you are progressive doesn’t mean you are going to vote with us 100% a time.”

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply