News

CA120: Next gov’s contest will be Reep on Dem

The Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey face off. (Illustration, Victor Moussa/Shutterstock)

The Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey face off. (Illustration, Victor Moussa/Shutterstock)Yours truly made a bold bet that California’s U.S. Senate contest in 2016 wouldn’t result in Democratic intraparty runoff. I was confident in my prediction a year before the election because of the percentage of the state’s Republican registration and the higher propensity turnout for Republicans in primary elections. The odds were entirely against it.

However, all this went south when 17 candidates lined up. Rather than a typical election where Republicans rally behind one of their potential nominees, the support from Republicans was diffused among multiple candidates, and many Republicans just didn’t vote in the contest because there wasn’t a clear choice for them.

To exacerbate this, the primary — which was supposed to be pivotal for Donald Trump — ended up being a dud on the Republican side and an energizing last stand for Bernie Sanders on the Democratic side.

In the end, the unlikely happened, and I was on the wrong side of history.

As we look forward to the 2018 election cycle, this experience from the U.S. Senate race is square in the middle of our rear view mirror.

Lost, along with my pride, is some perspective about the unlikely nature of that event.

Some are not only asking when this will happen again, but whether this is the presumptive new normal.

It’s as if they need convincing that all statewide general elections aren’t going to start being exclusively Democratic.

It is likely that by 2018 the total voter population will reach 20 million, and the Republican Party could be less than a quarter of that total.

In this, the coming governor’s race is Exhibit A.

With a flood of expected gubernatorial candidates on the Democratic side, and a lack of Republican candidates lining up for 2018, many are convinced that we are headed for another Democratic intraparty runoff.

So, again, it is prediction time.

And again, I will go with the math and say the general election of the 2018 governor’s race will follow tradition and feature a Democrat versus Republican. If you’d like to weigh in on this, click here.

There definitely are reasons I could be wrong.

California Republicans have dropped as a share of the registered voters to a record low 26%. The GOP has averaged just 17% of all new registrants since January. Currently, voters who chose a third party or register as “independent” are the second largest portion of the electorate, behind Democrats who are holding steady just under half the state’s voters. This pool of nonpartisans is expected to grow significantly with the full implementation of the new DMV registration rules which are scheduled to take effect in mid-2017.

It is likely that by 2018 the total voter population will reach 20 million, and the Republican Party could be less than a quarter of that total.

This makes it relatively easy to see cases in which the 75% combined share of Democrats, independents and third-party voters launch two well-funded, high-profile Democrats into a November runoff.

Primary elections are dominated by partisan voters. In particular, Republicans are buoyed by higher participation rates than Democrats or independents.

Several Democrats apparently see themselves as the next governor, and they are lining up for 2018. We have announcements from Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, State Treasurer John Chiang, and former Superintendent of Public Instruction Delaine Eastin.

And more could still jump in, including Senate Leader Kevin DeLeon, former State Controller Steve Westley, and billionaire environmental advocate Tom Steyer, to name just a few.

At the same time, the two highest profile Republicans in the State, San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer and former Fresno Mayor Ashley Swearengin, have both demurred.

Their public statements against running could obviously be rescinded, but their absence appears to leave Republicans without a strong option. One long-shot was that Kevin McCarthy would run, but his position in the Congressional leadership with a Republican administration is unlikely to be tossed aside in exchange for a long-shot run for state office.

Even if Republicans are only 25% of the registered voters by 2018, we can expect them to be around 35% of the voters casting ballots.

Stop reading now, and my prediction seems pretty foolish. But, looking more closely, the math and history of California’s top-two primary are actually with me.

Here’s why:

Primary elections are dominated by partisan voters. In particular, Republicans are buoyed by higher participation rates than Democrats or independents.

Two factors contribute to lower turnout for independents in primaries: They are less interested in partisan contests (presumably why they didn’t register with a party to begin with) and they consist of younger and less engaged voters. Their non-participation in primaries effectively magnifies the strength of those who are more partisan and older.

Add to this the fact that low-turnout elections are dominated by whiter, older voters, and homeowners from higher income communities, which further gives an added advantage to Republicans and some Republican-leaning independents.

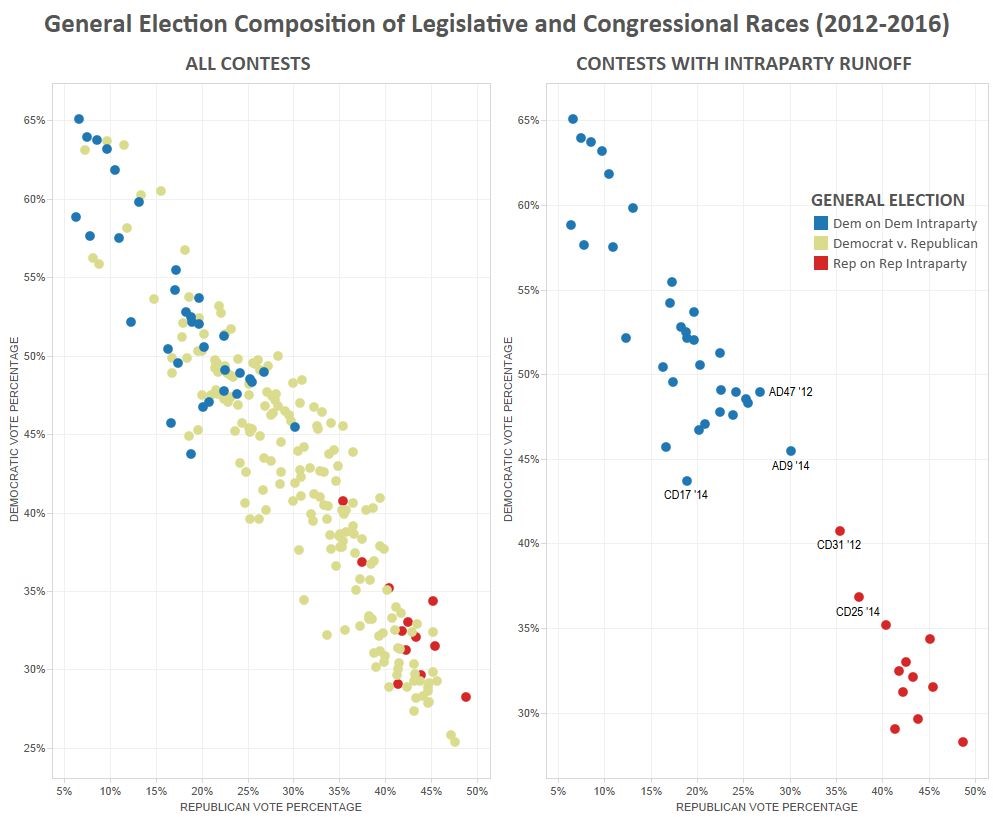

During these three election cycles since 2012, there have been 459 contests, of which 230 had multiple candidates from both political parties and which could have resulted in an intraparty runoff.

Even if Republicans are only 25% of the registered voters by 2018, we can expect them to be around 35% of the voters casting ballots. Add to this the nonpartisan voters who regularly vote for Republican candidates, and we can expect a low-turnout gubernatorial primary election to have 40%-to-43% of the electorate reliably voting on the Republican side of the ticket.

These partisan voters generally stay within their partisan camps. Despite all the talk of ticket-splitting and crossover voters, the fact is that 85-to-90% of votes are siloed within their political parties. This means that in a low-turnout gubernatorial primary, Republican candidates will get more than 40% of the votes, with Democrats getting under 60%.

This kind of math makes it hard to envision a situation where a Republican candidate doesn’t at least slip into the second spot. And a single Republican frontrunner, facing a divided Democratic field, could actually finish first.

Looking more closely at recent history can give more depth to this analysis.

Over the past three election cycles, we have built a rather large dataset of contests for Assembly, Senate and Congress under the state’s blanket primary system.

During these three election cycles since 2012, there have been 459 contests, of which 230 had multiple candidates from both political parties and which could have resulted in an intraparty runoff.

Of these, 45 resulted in an intraparty runoff — 33 Democratic and 12 Republican.

The following chart shows all these contests, and then, for clarity, just the intraparty runoff general elections. A detailed infographic is available here.

Looking at this data we find:

—Intraparty runoffs exist at the ends of the spectrum – races with lopsided registration and strong Democratic or Republican advantages.

—Only one intra-party contest has been held in an area where that party was not the majority. The aberration was the very unique Congressional District 31 race in 2012, when several Democrats split the primary vote. The result was so close that then-incumbent Republican congressman Gary Miller’s 27% in first place was just 2,500 more votes than the third place finish for Democratic Redlands Mayor Pete Aguilar. Miller and Republican State Senator Bob Dutton squeaked into the General Election. But the result was short lived, and Aguilar was elected in 2014 and recently re-elected with ease.

–The likelihood of a Democratic intraparty runoff increases dramatically when you get into districts with more than a 40-point Democratic advantage. Of the 18 contests with this high of a partisan advantage, 10 became intraparty Democratic runoffs, a rate of 55%. For those with between 20 and 40-point Democratic advantage there have been 75 contests, and 23, or 30% of those, resulted in intraparty contests.

–Republican intraparty runoffs are much less common, with only 12 coming from primaries that weren’t exclusively Republican to begin with. Of those, seven came from districts where there was a greater than 10-point Republican advantage, just more than half. But that is among 32 contests, meaning that only 22% of contests with a 10-point or greater Republican advantage resulted in an intraparty General. Unlike Democratic districts with large concentrations of partisans, there are only three districts with a Republican advantage of greater than 20-points.

–Democrats currently have an 18-point advantage statewide. If you look at partisan advantages at the district level there have been 83 contests in which the Democratic advantage was less than 20-points. And of these, only one, the 2014 Assembly District 9 race between Jim Cooper and Darrell Fong, a race with large Democratic funding, and an overlapping Dem on Dem Senate race, resulted in an intraparty runoff.

–Looking at it another way, there have been 27 multi-candidate primaries in districts where Republicans were between 25-27% of the registered voters, right around the current 26% Republican registration statewide. Of these, only three resulted in a Dem-on-Dem race. These were:

-

- AD 47 (2012) where Democrat Cheryl Brown was able to gain a second spot against former incumbent Assemblymember Democrat Joe Baca Jr. who had a unique appeal to Republican voters but was losing Democratic support through controversies.

- SD 6 (2014) two incumbent Democratic Assembly members, Richard Pan and Roger Dickinson, with millions of spending, overcame two unfunded Republican candidates to make the November runoff.

- CD 30 (2012) two incumbent members of Congress, Howard Berman and Brad Sherman progressed to a runoff after one of the most expensive and high profile primary elections in the country’s history.

So, while there are a significant number of intra-party runoffs, these generally have similar factors that contribute to what is still an uncommon outcome in our primary elections. This begins with a very partisan skewed electorate, where one party has enough votes to launch two candidates out of the primary and the minority is either divided, or too weak to support their nominee. Where the electorate is less skewed, some extra circumstances having to do with a dramatic inequality of funding or profile of candidates is necessary.

In the U.S. Senate race, Republican Chair Jim Brulte stated that the lack of a nominee was actually a strategic win for the Party.

At the statewide level, the current rates of registration for each party suggest that we are in a territory where intraparty runoffs will still be extremely rare.

It would take a repeat of circumstances like we saw in the 2016 U.S. Senate primary where the lineup of candidates was much more like the Berman/Sherman or Pan/Dickinson contests, with two heavily funded front-runners from the majority party, and a cratering of the Republican coalition among several underfunded candidates.

But, aside from all the numbers and the history of our blanket primaries in district elections, the strongest argument for a Republican making the 2018 runoff is motivation.

In the U.S. Senate race, Republican Chair Jim Brulte stated that the lack of a nominee was actually a strategic win for the Party.

Instead of having Harris raising money and organizing for other Democrats statewide, even nationally, she and her backers were forced to spend time and resources on the Senate contest. The motivation to get a Republican into that runoff just wasn’t there because it wasn’t going to drive Republican turnout, was a huge long shot and would force Republicans to spend money in a virtually unwinnable race.

While Republicans had a national Presidential contest as a motivating force at the top of the ticket, in 2018 the Governor’s race will be the biggest game in town. Having no Republican candidate in the November runoff would be detrimental to overall Republican registration and turnout in a way that was not a factor from the U.S. Senate contest. Lower turnout could cause great harm to down-ticket legislative and congressional races and could even harm conservatives in local and statewide ballot measures.

While I have been told to not bet on these things, I feel confident in this bet because I’ve got two strong arguments: The numbers are on my side – statewide intraparty runoffs will be extremely rare as long as the Democratic share of the electorate doesn’t grow considerably; and, most importantly, Republicans know that conceding the Governor’s race to a Democrat vs. Democrat runoff would be a partisan disaster with wide-ranging long-term negative consequences up and down the state.

Jim Brulte himself will be motivated to ensure I win this bet.

—

Ed’s Note: Paul Mitchell, a regular contributor to Capitol Weekly, is the founder of the CA120 column and the vice president of Political Data, which markets campaign information to to both major parties. Data compiled by Alan Yan.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply