Analysis

CA120: Alabama election a wave — or just a ripple?

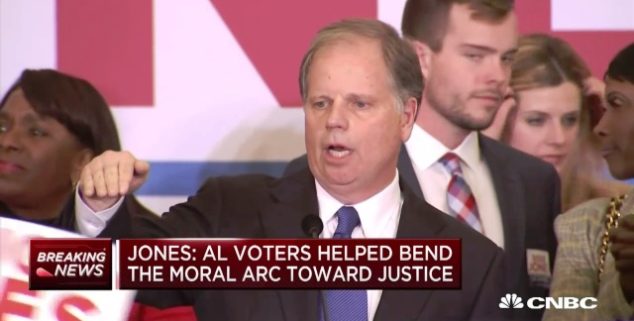

Democrat Doug Jones on election night in Alabama, declaring victory over Republican Roy Moore in the U.S. Senate special election. (Photo: Screen capture, CNBC)

Democrat Doug Jones on election night in Alabama, declaring victory over Republican Roy Moore in the U.S. Senate special election. (Photo: Screen capture, CNBC)The recent U.S. Senate election in Alabama marked for many political observers the first striking evidence that the coming year will bring a “wave election” that could wash Republican majorities out of Congress and trickle down to gubernatorial and legislative seats.

It seems like a big turnaround based on just one election result.

Just a year ago, Democrats were dealing with the fact that they had lost a Presidential election that everyone thought was in the bag. Not only did Democrats believe they had a built-in Electoral College advantage, they had lucked out by having Republicans nominate the seemingly un-electable Donald Trump instead of the cross-over voter magnets of Marco Rubio or John Kasich.

The taking of the White House in 2016 capped off a series of accumulated Republican gains since 2010 – primarily in non-presidential years – which has taken them to the highest level of single-party control since the 1920s.

Not only do they have majorities in Congress, they have a complete lock – from the governor’s office to both houses of the legislature — in 26 states.

Democrats are hoping to rather quickly flip this script by electing a majority in Congress, and, more importantly for the long run, regaining state houses and governor’s offices before the next redistricting in 2021.

Democrats might very well be headed for a wave election in 2018, but for real evidence we need to look deeper.

In this environment it is easy to see why the Alabama victory was so cathartic and thrilling for the Left.

It entailed winning a seat previously held by Jeff Sessions in a state so conservative that the baseline would be a 28-point Republican victory, and the losing candidate was an accused pedophile endorsed by President Trump.

Yet, Alabama isn’t, in and of itself, a recipe for Democratic resurgence in 2018, unless Republicans continue to find and nominate individuals as flawed as Roy Moore.

Democrats might very well be headed for a wave election in 2018, but for real evidence we need to look deeper – not just at the Alabama election, but to other races where Democrats might not have won, but where they over-performed nonetheless.

And that evidence isn’t hard to find.

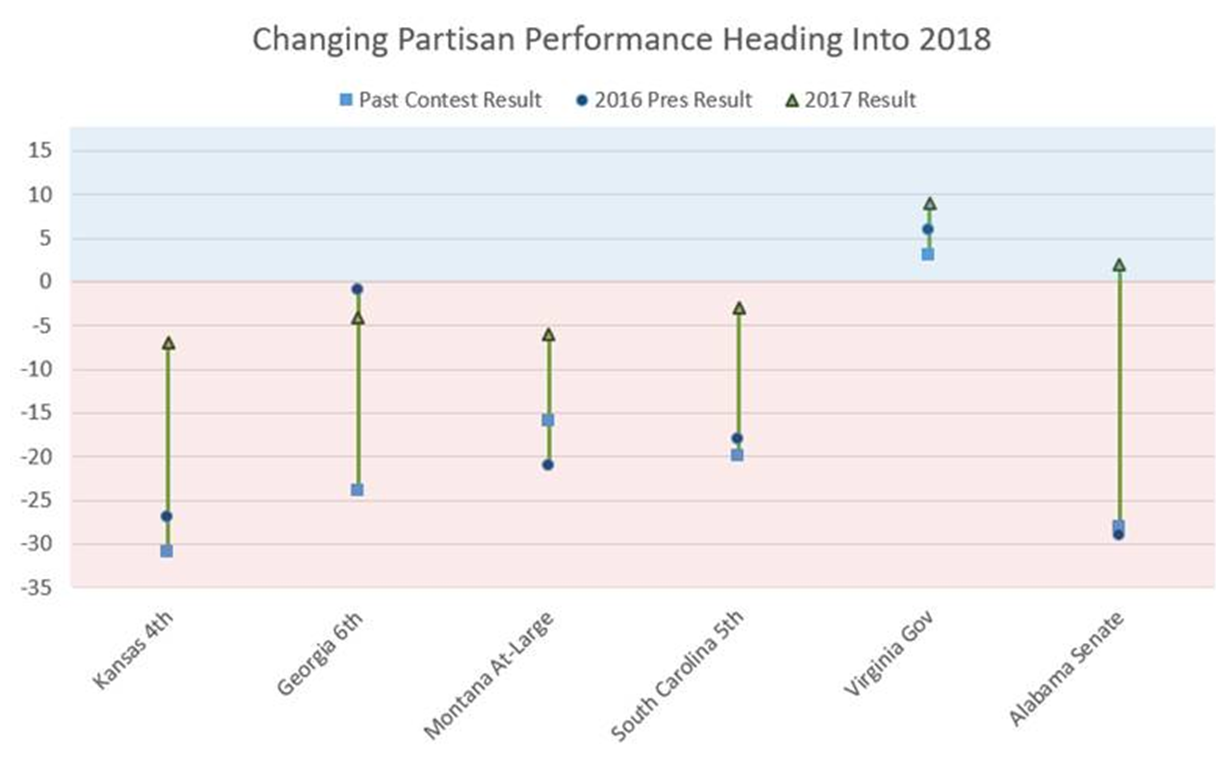

If you look at a larger set of election results from 2017, you can see Democratic candidates performing 10-points over their levels in the 2016 presidential contest, and 13.5% over their baseline from the prior elections in either the 2014 or 2015 non-presidential election cycles.

If you look at the Alabama election within the context of other 2017 races you can make a back-of-the-envelope calculation that the win for Doug Jones was approximately 40% from Democratic over-performance generally, and 60% from the fact that Moore was possibly the worst candidate nominated by a major political party in our lifetimes.

But, even with this potential wave, there are reasons to be circumspect about a full Democratic takeover in 2018.

Alabama was an outlier, but not an outlier that breaks against the national trend. And it is this trend – not the one instance of one upset result in a December special election – that should have Republicans worried.

The idea of a Democratic wave election in 2018 could have been predicted the day President Trump was elected. If Hillary Clinton had won, we would probably be talking about a pending Republican wave election. Whoever won the White House would likely have seen a bad first mid-term election, a phenomenon that has occurred 16 of the last 18 times, costing the party in power an average of 22 seats per cycle.

But, even with this potential wave, there are reasons to be circumspect about a full Democratic takeover in 2018.

Nationally, congressional seats have a 5.5% Republican advantage over the base election result, largely due to their control of the 2011 redistricting in most states.

This means that a wave election which is plus-5 points Democratic nationally would actually be a losing election cycle. The current projection for 2018 is a 7-point Democratic advantage, which will be tight.

A 10-point wave as we have seen in 2017 would predict Democrats taking over the House, but the U.S. Senate would require an even heavier lift, winning very challenging seats in Nevada and Arizona, and holding every Democratic held state.

The most vulnerable Republican congressional member in California, according to the Cook Political Report, is Darrell Issa in the 49th district, who was able to hold on to his seat in 2016.

In California, prospects for big Democratic sweep – even picking up Republican held congressional districts that voted for Hillary Clinton – is not going to come easy.

While other states saw huge gains for Republicans, presumably making for some increasingly vulnerable seats that cannot withstand a Democratic wave, in California we have a paltry number of potential targets, relegated to some of the most Republican leaning areas of the state.

Several swing congressional districts in California — like those in Sacramento (CA-7), the Inland Empire (CA-31 and CA-36) and San Diego (CA-52) — are competitive, and were won by Democrats in 2012, then held through 2014 and the strongly Democratic election year of 2016.

The most vulnerable Republican congressional member in the state, according to the Cook Political Report, is Darrell Issa in the 49th district. He was able to hold on to his seat in 2016, despite the fact that his district saw registration that was 4-points less Republican and 3-points more Democratic, and had higher Democratic turnout than 2012 and its highest Latino turnout ever.

And, as has been reviewed before in this column, new registrants from the 2016 election cycle are not likely to be turning out in droves in 2018, and the past history of gubernatorial elections does not appear promising.

So, while Alabama alone doesn’t portend an end to Republican control in 2018, it does have within it the signs of a Democratic wave nationally that has been evidenced in multiple elections in 2017.

The question of what it will mean in the win-loss column for congress, state houses and governor’s races in 2018 is still an open question. The bottom line is that the impact in California specifically could be a bit more challenging for Democratic gains than the rest of the country.

—

Ed’s Note: Paul Mitchell, a regular contributor to Capitol Weekly, is vice president of Political Data and owner of Redistricting Partners, a political strategy firm.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for The Roundup, the free daily newsletter about California politics from the editors of Capitol Weekly. Stay up to date on the news you need to know.

Sign up below, then look for a confirmation email in your inbox.

Leave a Reply